An Eclectic Circus

Chapter 38

As the boulders smashed down from the mountain’s hand

The conveyor belts beneath the mid Atlantic ridge turn and turn again as they have been turning for millions of years, pushing Britain and America apart. Pushing the whole of Britain, Europe, and Africa away from the Americas. Day after day, year after year, inch by inch, the Americas are pushed away from the old world. We send bands over to New York, San Francisco, and everywhere between and hope that they’ll bridge the gap. Some do, some don’t. Some poor souls, like the Pistols, break themselves in pieces trying to break America. And the gap widens.

The North American plate continues its relentless crawl away from the European plate, bullying its way over the Pacific plate. In reality, like all bullies, the North American plate is picking on the little guy, a small wee microplate between the North American plate and the Pacific plate, trying its hardest to grow itself, but getting overrun by Washington and Oregon. Down in California, the Pacific plate and the North American plate push against each other, shoulder to shoulder, jostling for position like schoolboys in a dinner queue, not really damaging each other, just causing a few cracks to appear in San Francisco and LA – earthquakes that are murderous for animal life on the surface but just noise for the big plates. Further north, things are more vicious. The North American plate pushes itself over the plucky little Juan de Fuca plate forcing the underdog down towards the innards of the planet.

Like a dying animal that lashes out in fury with its last breath, the drowning plate passing under the North American plate causes the Earth’s mantle to melt and rise as magma. The magma rises up through the mantle, up through the crust of the North American plate, and, finding the weaknesses from previous magma journeys, breaks out at the surface in a mighty explosion, destroying the quiet beauty of the Mount St Helens National Park, taking the top off the beautiful snow capped mountain that Pacific Northwesterners had been gazing at lovingly for years, spreading vicious hot gases, molten lava, and fractured lumps of the old mountain over the gorgeous countryside that Pacific Northwesterners had been hiking over for years, clogging up with debris the pristine waters of Spirit Lake that Pacific Northwesterners had been sailing on for years, and covering the Pacific Northwest and the Pacific Northwesters with souvenir ash.

The mountain will recover. With orogeny and erosion, it will regain its former shape. The snow will return. The lake will clear. Plants will return to the ground around the mountain. Trees will come back and the National Forest will return to its former glory. The mountain survives. The mountain doesn’t care for the humans that may come and go. The mountain has been here for millions of years and will last millions more. The people of the Pacific Northwest carry on their short frantic lives unnoticed by the mountain, undetected by the Earth.

We carry on. Pall opens the door to my room and walks in. It’s the day after the Teardrops gig. I’m working – reading up sommat or writing out notes. It’s getting late – just after ten.

“Turn the radio on” is all he says.

There is only one radio to turn on. John Peel. He’s playing Joy Division. No surprise there. New Dawn Fades. I don’t know why Pall needs me to listen to this now. I’ve got the album. I play it all the time.

I look at Pall. He looks frightened. He says nothing. His eyes stare at me, pleading with me to help him, like I’m his big brother. Pleading with me to fix whatever has gone wrong.

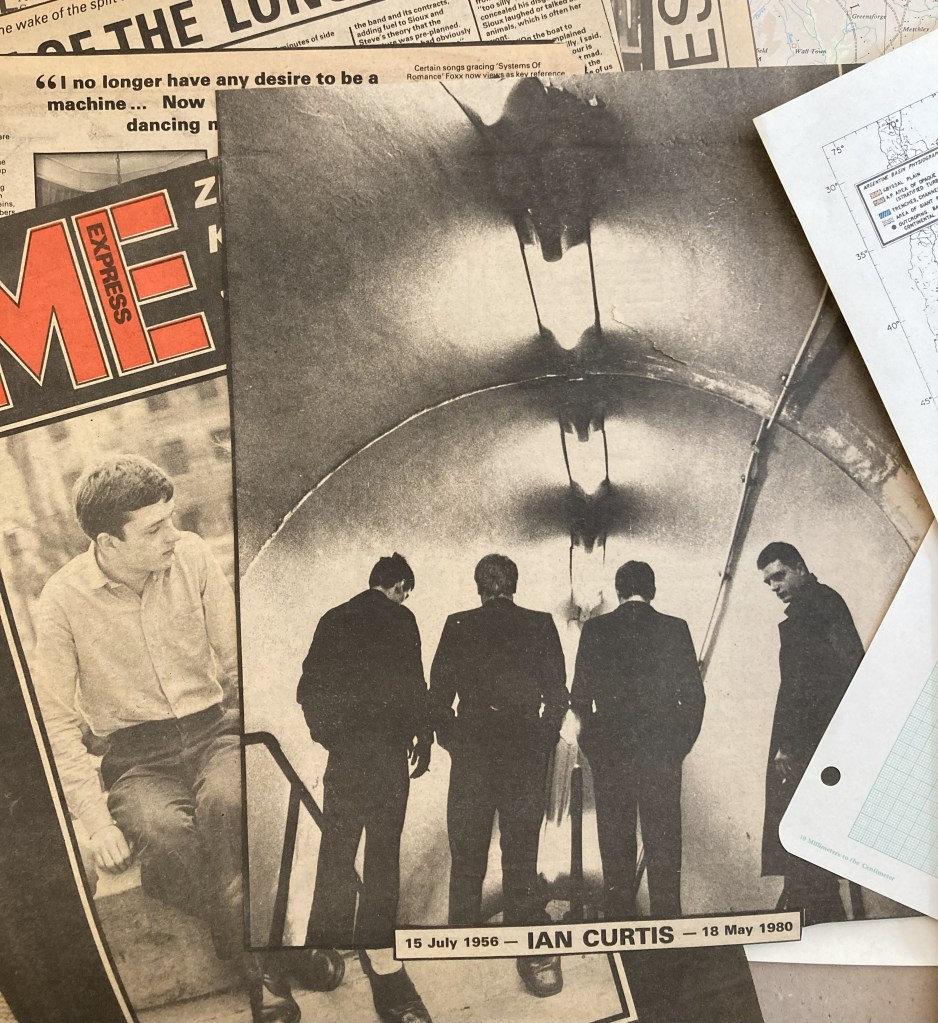

Then Peel says one simple sentence and I understand. I understand why Pall wants me to listen to the radio. I understand the look in his eyes. I understand why he wants me to fix this. For the past 12 months, we’ve listened to every word Ian Curtis sang. We’ve bounced and grooved and rocked and chilled and relaxed and reflected and wondered and worried and despaired along with the music. We’d watched them in awe, Steve Morris at the back propelling them forward; Hooky on one side, Bernie on the other; Hooky occasionally taking a step left or right, leaning over trying to reach down to the bass by his knees, Bernie perfectly still over the guitar studiously ringing out the chords and riffs; all of them in shades of grey; and Ian Curtis nervously hanging onto his mike, eyes almost closed, his deep voice tolling out his lyrics. Ian Curtis, between the verses, frantically rooted to the spot trying in vain to jog away from what’s scared him. Ian Curtis metamorphosing into Gregor Samsa, awoken from uneasy dreams, on his hind legs, flailing the other four legs in the air trying to beat away the nightmares of the future. We loved that band. Now we were in shock. We feared their passing. We’d never see them again. Never listen to their new tracks. Never know how they’d develop over the years. We were mourning the death of the music.

We didn’t know Ian Curtis. We didn’t know about his life. We didn’t know what he went through. We didn’t understand what had happened to Ian Curtis, to his wife, to his family, to his mates. How could we?

The Earth doesn’t care. The rocks don’t care. Mount St Helen’s doesn’t care. But we care. We all matter. We are all the centre of our own universes. We all have our own issues. We’ve all got missing parts.

What were you worrying about Pall? Your exams? Whether you really wanted the responsibility of the career your course was mapping out for you? And Gav: worrying about how your Dad would react when you told him about your plans. And Nessie, worrying about why everyone was so set against you having fun the way you wanted to have fun. And Pete, scared of letting your real feelings show so putting on a performance to cover them up. And all those folk in Deacon Brodie’s wondering whether they’ve got a future.

And yet the North American plate rumbles on, inch by inch, slowly opening up the Atlantic. Slowly moving west. An almighty shrug of indifference.

In their tribute after Ian Curtis’ death, Paul Morley & Adrian Thrills write “The very best rock music is art”. That’s true. It can move you, change you, frighten you, lift you the same way Picasso or Mondrian or Orwell or Hardy or Tchaikovsky or Sibelius can. It can make you laugh and it can make you cry. It can make you want to jump up and touch the clouds or run down the street screaming. It can also make you dance which puts it one up on most art and all architecture. Morley & Thrills said “Joy Division make art. Joy Division make the very best rock music.”

Joy Division made the very best art.

Ian Curtis was 23 when he died. He was only a year older than me.