Editions of You

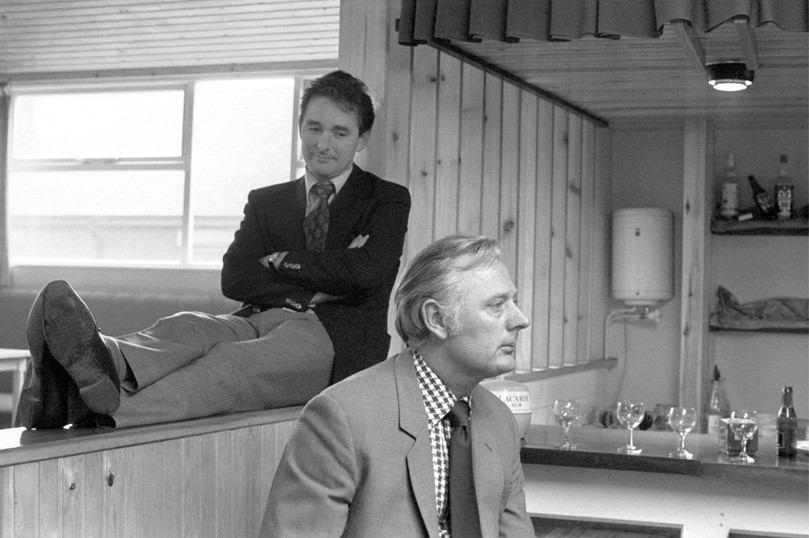

“We’ve got a little fat guy who’ll turn him inside out… A very talented, highly skilled, unbelievable, left-footed player.” [Brian Clough]

“John Robertson was like Ryan Giggs but with two good feet, not one. He had more ability than Ryan Giggs, his ratio of creating goals was better and overall he was the superior footballer” [John McGovern]

“One of the finest deliverers of a football I have ever seen – in Britain or anywhere else in the world – as fine as the Brazilians or the supremely gifted Italians.” [Brian Clough]

“He was slower even than me, but that little fat bastard was a magician.” [Larry Lloyd]

“If you gave him the ball and a yard of grass he became an artist. He was the Picasso of our game.” [Brian Clough]

“Sir Stanley Matthews and Sir Tom Finney are knights of the game but Robertson is them and then some.” [Jimmy Gordon]

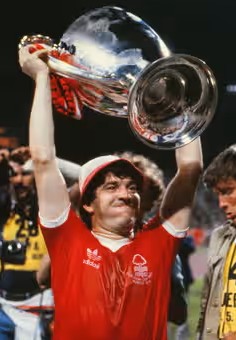

A Song for Europe

John Robertson stands like a colossus on the twin peaks of our greatest achievements. His genius shone through both of our European triumphs. His legacy will forever be remembered with those two stars on our shirt. His name will be shouted out from every history of our club that is ever written.

If it Takes All Night

John Robertson was a very talented, skilful footballer. Yet, I don’t think I’m the only Forest fan who saw Robbo back in the autumn of 1971 and wondered whether he’d ever make it. He was playing somewhere in central midfield and, as the commentary on one of the games notes, “working hard without making any positive contribution”1. Over the course of his first five or six years at Forest, he never hit the heights he was capable of. It took two exceptional people to give him that extra and turn him into the world class footballer that he became.

Robbo had the talent. But as well as inspiration and perspiration, Robbo needed luck, opportunity, encouragement, and belief. Clough and Taylor had the emotional intelligence to give him what he needed and get the best out of him. In return, Robbo gave Clough and Taylor their two greatest victories.

Just Like You

Robbo was born and brought up in Uddingston, a small town on the outskirts of Glasgow. When he was growing up, Uddingston was famous for the Tunnock’s Teacake, a little round ball of sugar, and Jinky Jimmy Johnstone. Robbo was raised as a Rangers supporter, but revered the little Celtic winger with whom he shares so much2. Robbo and Jinky were raised about a mile from each other, they could both turn defenders inside out, they both won European Cup glory, and were both voted their club’s greatest ever player. There’s a statue of Jimmy Johnstone up in Glasgow. There’ll be a statue of John Robertson in Nottingham one day. It’s just a question of time.

Spin me round

Take a look at Jimmy Johnstone – there’re plenty of videos on line – and you’ll notice similarities between the two playing styles. Swap the hoops of Celtic for the Garibaldi and you’ll recognise the low centre of gravity of Robbo diligently protecting the ball like a tourist shielding their fish & chips from seagulls on Scarborough beach. You’ll see Robbo’s twin twinkly-toed feet in total control of the ball, never more than a couple of inches from his boots. You’ll remember him mesmerising full backs like a hypnotist putting them to sleep and then leaving them grasping at thin air, puzzled and bamboozled like a punter who’s been tricked by a light fingered dipper.

More than this

Robbo could do all of that and more. He had a sudden burst of speed which could leave his markers standing as embarrassed as a hapless passenger at the Wollaton bus stop watching the 36 rush by into town without stopping. He had an unexpected change of direction which would twist and turn the full back like a soggy towel being wrung out to dry. He had a library of tricks to dumbfound the defence and leave them searching for the ball like my wife desperately trying to solve the mystery of where she might have left her phone.

Manifesto

The dream started in 1960. That year, the European Cup final was played at Hampden. It has gone down in Scottish folklore as one of the all time greatest games played there. 127,000 were in the ground and millions more, including a seven year-old Robbo, watched on TV at home as Real Madrid scored seven to win the cup. Not many teams can score seven at the top level3. That final, in particular the performance of Madrid’s Ferenc Puskas, sparked Robbo’s love of the game. When he started to play, Robbo was naturally right footed; however, he practiced and practiced with his left foot so he could emulate Puskas. At school, he developed into a very good young footballer. As a teenager, he joined the famous Drumchapel Amateurs on the other side of Glasgow – a stepping stone for many youngsters through the years, including Archie Gemmill, Asa Hartford, David Moyes, Alex Ferguson, and others.

Could it happen to me?

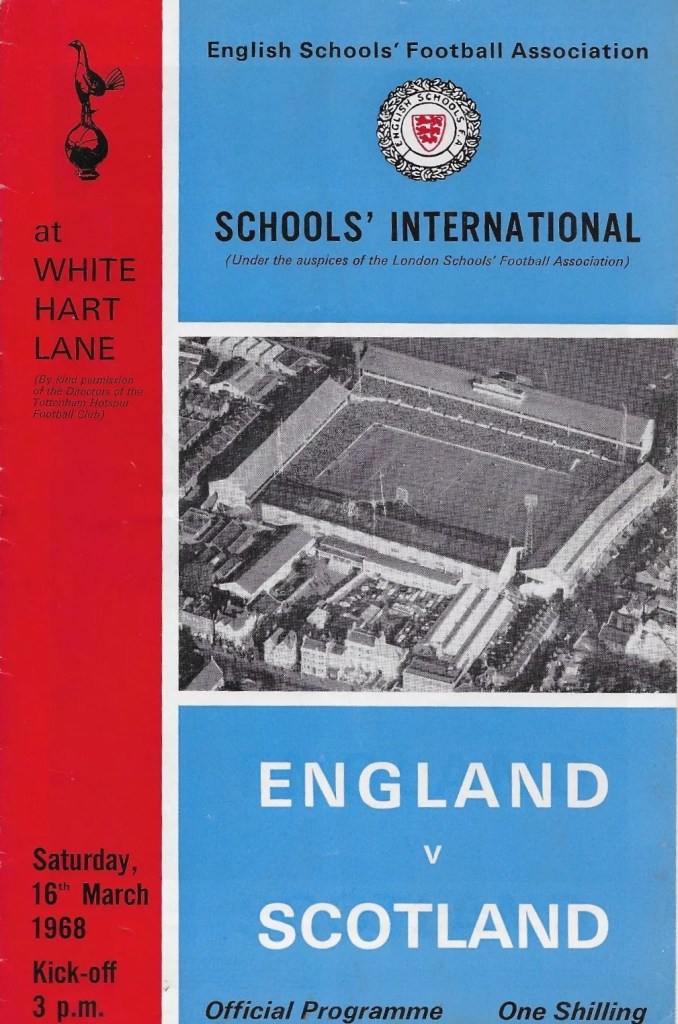

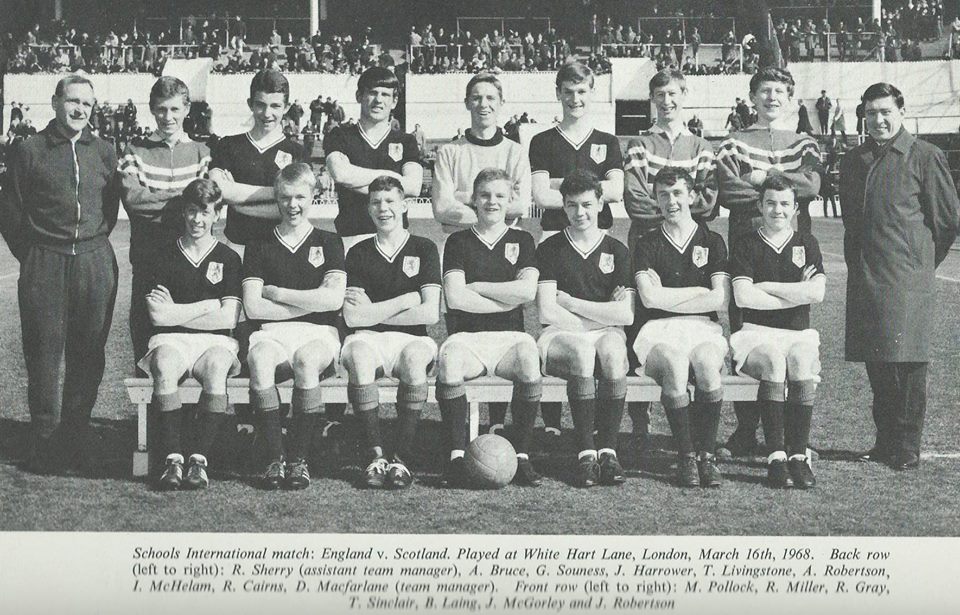

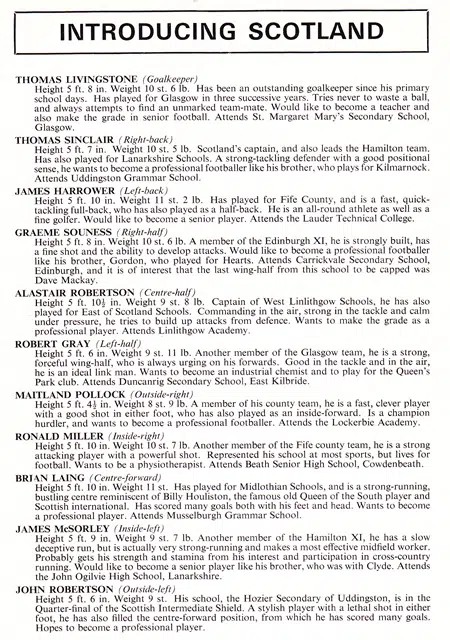

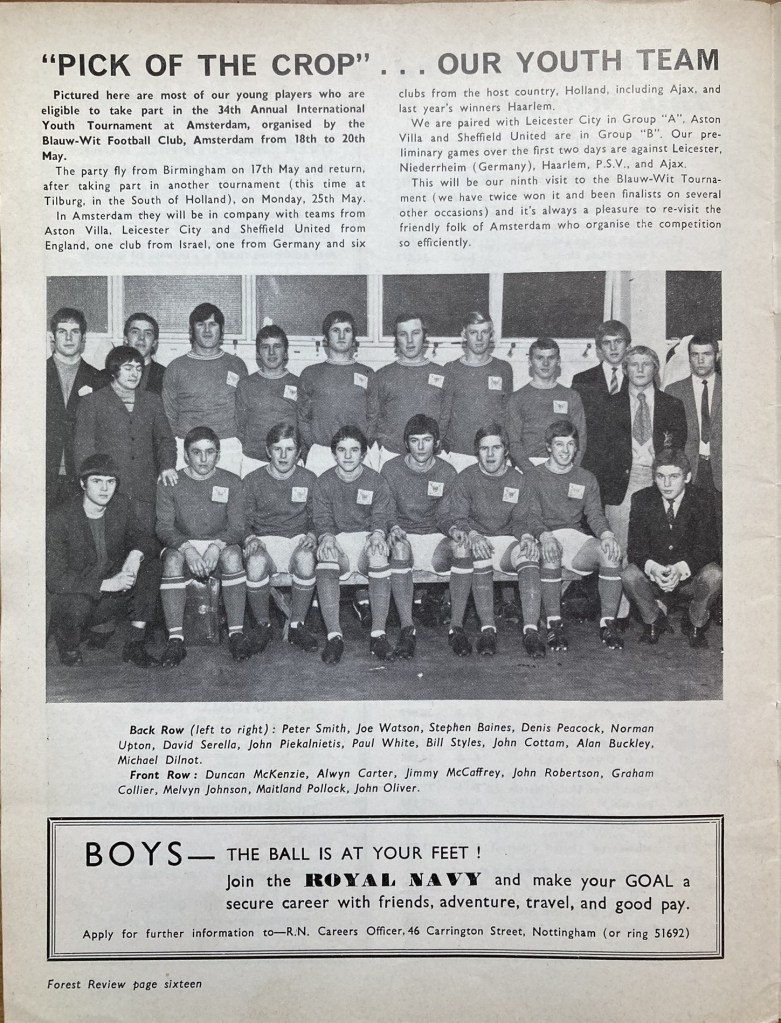

In 1968, he played for Scotland schoolboys a few times, including two games against England: one at White Hart Lane where he provided the cross from which the only goal of the game came and one at Ibrox where he also provided the cross for the only goal of the game. Also in the Scotland squad were Alistair Robertson – future West Brom stalwart and Graham Souness – future member of the Liverpool team beaten in that European Cup first round tie. Also also playing was a lad called Maitland Pollock. Recognise the name?

All I want is you

There were a couple of teams interested in signing Robbo at that stage: Partick Thistle and Cardiff City. Then Forest turned up in the shape of Johnny Carey’s assistant manager Bill Anderson and legendary centre half Bob McKinlay. Robbo says he had decided that he wanted to play in England as he reckoned that was where the future was, so he headed down to Nottingham in May 68 with fellow schoolboy international Maitland Pollock who Forest had also signed. The fact that we had Jim Baxter on our books at the time may well have influenced Robbo in joining us. Robbo, of course, would have loved watching Jim Baxter, especially after seeing him take the mick out of England when Scotland won the unofficial World Cup final at Wembley in April 19674.

Not many folk will tell you that Baxter was a success for Forest, but if he played a part in Robbo signing for us, then the fee we paid for Baxter was worth every penny.

[By the way Matt Pollock stayed at Forest for another 5 years but never made the first team. He eventually found his level and enjoyed two reasonable years at Pompey.]

Robbo arrived in Nottingham as a raw 15 year old and ended up in digs with many of the other youth players, including a wee show off by the name of Duncan McKenzie. The next few years were a series of ups and downs for the club (mainly downs) as managers and players came and went (mainly “went” in terms of the quality players).

The Pride and the Pain

Robbo’s fortunes over those next few years were similar to those of the club as he travelled his slow tortuous route to the top. Things almost got off to a pretty hot start in August of 68 when he was asked to go into the changing rooms and rescue the first team’s belongings during the Main Stand fire that began during the Leeds United game. Robbo survived. The players’ suits didn’t.

By the end of that first season, he was a regular in our youth team alongside some other promising youngsters. In January 69, a week before his 16th birthday, he played his first game for the reserves, and had established himself in the reserve team by the end of the following season.

In October 1970 he made his first team debut, coming on as sub in a 3-1 home win against Blackpool and two weeks later played a full ninety minutes at Huddersfield wearing the number 6 shirt. Then a gap. His next league game was about a year later and he played a handful of games at number 10, a few at number 8, and a couple more at number 6. In one of those early games, Martin O’Neill made his debut, coming on as a substitute for Robbo and scoring almost immediately. But this was during the management of Matt Gillies who didn’t like playing kids. Duncan McKenzie was also left out. Quoted in John Brindley’s 20 Legends, McKenzie said ”It wasn’t just me who suffered … We had Alan Buckley, Graham Collier, John Cottam … Martin O’Neill and John Robertson… but Gillies didn’t want to know”

Stronger through the years

The arrival of Dave Mackay a year later (in the autumn of 72) saw Robbo become a regular and also being given the job of penalty taker; however, a torn knee cartilage in the summer of 73 kept him on the sidelines and he didn’t play first team football again until March by which time Dave Mackay had been headhunted by that lot up the road and replaced by Allan Brown.

Robbo had enjoyed playing for Dave Mackay who just told him to “go out and have fun”, but he didn’t get on with Brown, especially as Brown couldn’t get his name right. He was in and out of the team (mostly out), but he did play in the infamous FA Cup quarter final at St James Park. With Forest 3-1 up against 10 men, the game turned following a pitch invasion and some spineless officiating. On the journey home, Brown told Robbo & Martin O’Neill that he blamed them for our eventual defeat.

Out of the blue

Six years after coming down from Scotland, it seemed that John Robertson was going nowhere. Out of the Forest team and seemingly on his way out of the club. Brown tried to offload him to Partick Thistle. Fortunately for us and unfortunately for the Jags, the deal fell through. But one person did appreciate his talents. In the summer of 74, Don Revie invited Robbo to join his first England get together. Robbo would never contemplate playing for England, but I wonder whether he was tempted to go along and have a really good laugh at Revie’s expense.

Brown’s days were numbered. He was sacked in January 1975. Then Cloughie arrived.

Whirlwind

Robbo was immediately impressed by Clough’s entrance and drawn to the man who entered the changing room, rolled his sleeves up, and started to get down to business. However, Clough didn’t notice Robbo. Bringing Martin O’Neill in from the cold at the expense of Miah Dennehy was the only change Clough made for his first three games. Famously, Cloughie needed to have his card marked by local journalist John Lawson who recommended that Robbo and Tony Woodcock be given a chance. Cloughie listened and when our regular number 6, Paul Richardson, was unavailable, Robbo got the chance. He was still playing in centre midfield, as he had been, on and off, for the past five years. He’d always wanted to play there – he said “that way, I’d see more of the ball”. But he admits he only had half of the skills needed to hold midfield: “I was good on the ball, not so good off it.” Coughie still had to explain to Robbo how to play in the middle; however, he must have seen something because Robbo kept his place for the rest of the season. (Tony Woodcock would have to wait another 18 months to become a regular.)

Remake/Remodel

The next step towards the Robbo that we know and love came at the start of the 75/76 season when Cloughie moved him to the left wing. It also helped that we’d just signed Frank Clark. As Robbo says of Clark: “with his defensive qualities I hardly ever tracked back and he just gave me the ball and let me go and do my little bits here and there.” He featured in almost every game that season. However, it wasn’t until the summer of 76 that it finally clicked for Robertson. Peter Taylor arrived and one of the first things he did was give Robbo a massive kick up the back side.

If There is Something

It has often been said, not least by Clough and Taylor themselves, that Taylor was the one who identified the players and their particular talents and that Cloughie was the one who motivated them. Robbo’s story shows that reality wasn’t that simple. It was Cloughie who moved Robbo to outside left, yet it was only when Taylor came in at the start of the 76/77 season that Robbo got the motivation he needed in the way he needed it. On a pre-season trip to Germany, Taylor told him he was a waste of space and ordered him to pack his bags. Taylor said: “If you don’t want to put the effort in, you can go home …” then almost as an afterthought hinted that he may have a future, saying “I think you can play.” That last short sentence was enough for Robbo. It convinced Robbo that he could contribute to the team.

Bitter-sweet

Two months into the 76/77 season, disaster struck Forest when Terry Curran suffered a bad cruciate ligament knee injury. This was the player that all of us fans had invested our hopes in. At the time, Cloughie was quoted as saying that “promotion has just limped out of the door”. But Curran’s misfortune was an opportunity for Tony Woodcock and Robbo. Woodcock finally got his chance to play, a chance which he grasped with both hands. It also meant that Robbo took over the creative role from Curran: less of the heavy water carrying and more of the sublime wing play that was Robbo’s forte.

Triptych

From then on, he played in every game and never looked back. Robbo teaming up with Clough and Taylor was just like George Martin after he’d discovered Lennon and McCartney. Or Cobain and Novoselic finding Dave Grohl. Or the Temptations after they’d teamed up with Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong. Or Spock after he’d met up with Kirk and McCoy.

A Really Good Time

Robbo is out on the left wing with the ball. He leans left, he leans right, he rides an attempted tackle, he retains his balance and hovers above the muddy field like a wasp in mid air, then darts away to leave the defender alone and isolated like Billy No Mates waiting by the wrong lion at the wrong time on the wrong day.

We’ve all got the compilations. The ever-present highlights on the show reel. The all important contributions down the years.

- The first goal in the final of the Anglo Scottish Cup – the cup gave Cloughie’s Reds their first trophy.

- The winning goal in the League Cup final against Liverpool – the cup that gave us our first major trophy under Clough and Taylor.

- Waltzing round the keeper to slot home the third of four in our trouncing of Man U at Old Trafford – the day everyone stopped doubting that we’d be league champions.

- The all important header in the crazy first leg of the semi against Cologne that first European year.

- The cross from a corner for the winning goal in the second leg of that semi final.

- The cross for the goal in the first European Cup Final.

- The goal the following year that kept the European Cup in Nottingham.

Just another high

(So which was Robbo’s most important goal? He was doing a Q&A in front of a large crowd of reds a few years back. The host wanted to talk about the 1980 European Cup Final and spent a long time bigging up that game and Robbo’s contribution to it before asking Robbo to describe his most memorable goal. Much to the bemusement of the host and the amusement of the crowd, Robbo then proceeded to talk about a penalty he scored for Scotland against England at Wembley. It won the game and he still considers it his most important goal.)

Oh yeah!

Robbo had two good feet. The most famous cross in the history of Nottingham Forest was delivered by Robbo’s left foot. The most important goal Robbo scored for us came from his right boot. That goal in the 4-0 at Old Trafford with his left. His many penalties with his right.

He could make magic with either foot. He could put a cross in exactly the right spot for any forward. He could ping a pass as sweet as a Tunnock Teacake. He could execute a deadly free kick, standing next to the ball like a darts player on the oche, then delivering it right onto a forward’s head, like yer darts player dropping the arrows into double top. And he could score. Just shy of a hundred goals for us. Left foot, right foot, and even, once, famously, with his head5.

Both Ends Burning

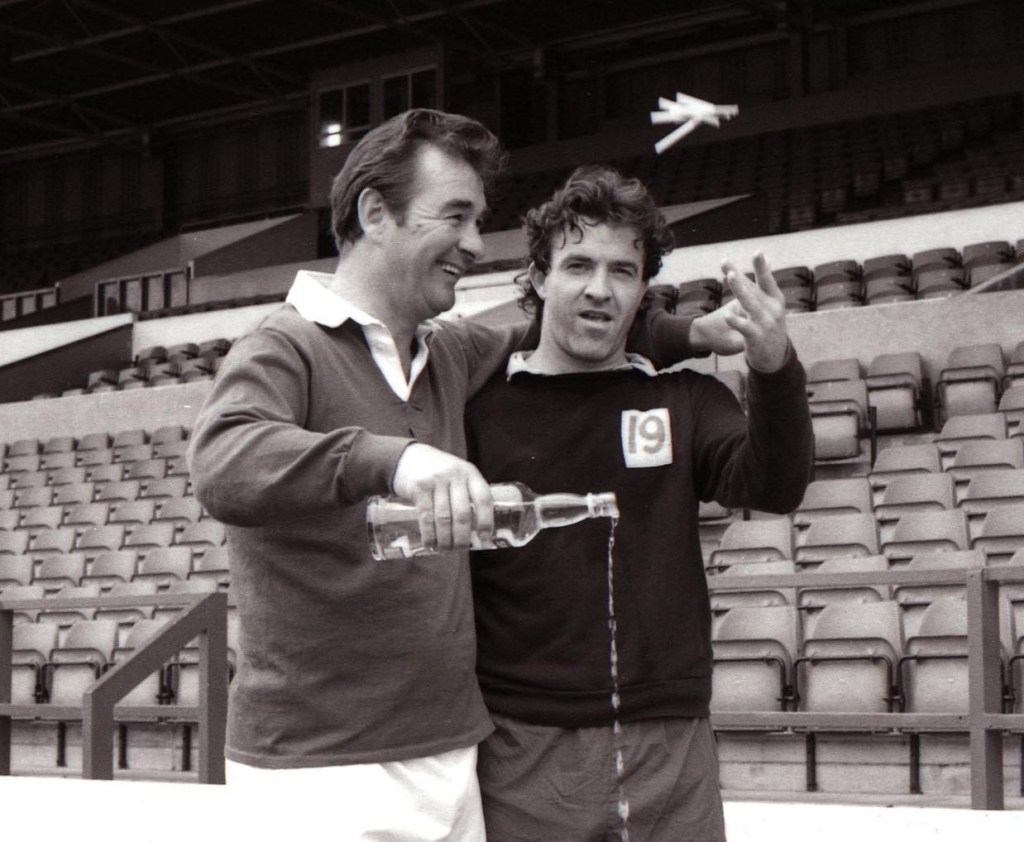

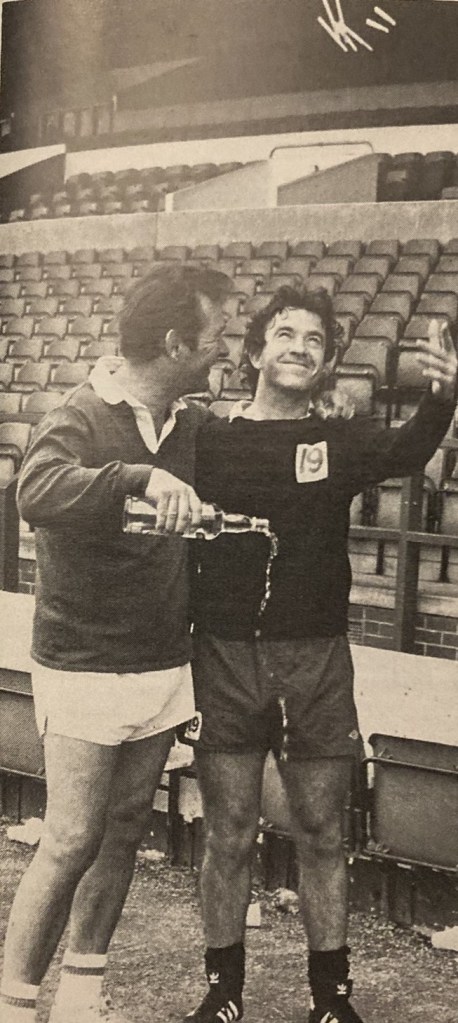

Cloughie had a lot of time and a lot of respect for Robbo. He probably saw a bit of himself there. They both had their weaknesses. They both liked to indulge themselves: Robbo with a fag, Cloughie with a drink. In 1982, they had a £100 bet with each other that they could break their habits. But, they both knew that neither of them could manage it. Not that Robbo’s smoking habit cost him in terms of fitness. He played the full 90 minutes in all of the 62 games we played during the 77/78 season and the full 90 minutes in all of the 71 games we played in the 78/9 season. (That includes mid-season friendlies. And if you know Cloughie, you’ll know he insisted that the first team turn out and give 100% in those friendlies.)

Would You Believe?

Robbo and Cloughie were made for each other. Robbo had the skill set Cloughie’s team needed. And it’s clear that Clough knew exactly how to motivate Robbo. He knew that Robbo mostly needed to feel wanted, to have someone put an arm round him, to be encouraged to play, to know that someone believed in him. We all need that sometimes. Someone to look after us when we’re down. To make us feel important. For Robbo, Clough was that person. Even when Cloughe took the mickey out of him, Robbo knew that it was done in a friendly way. With Clough, it was always done with a smile. But Cloughie also had the exact words to get the best out of him.

The End of the Line

Then in 82 & 83 it started to go wrong. The emotional intelligence that had been so important in the Taylor-Clough-Robertson triumvirate went missing. New signing Justin Fashanu wasn’t able to play in Forest’s style. Robbo didn’t enjoy playing with him. Clough had been sceptical about the signing and blamed Taylor. Clough and Taylor should have talked things through and agreed to put it behind them, but we don’t talk about stuff, do we? Their relationship started to fall apart and Taylor’s book about him and Clough didn’t help. Taylor decided he was past it and quit. Then, realising he missed the game, went back into management down the road.

Bitters End

Robbo was feeling old (at 30!) and was worried about a new contract. During the 82/3 season he spent more time playing in centre midfield with Colin Walsh playing on the left. Robbo was still contributing and doing all the stuff we remember him for, but when Walsh got the number 11 shirt, Robbo started to worry about his future. One word from him to Cloughie asking for reassurance or one word from Cloughie to Robbo to remind him how important he was would have resolved all of the questions. But we don’t talk about stuff, do we? Robbo jumped ship, joined Taylor down the road, and then regretted it from the moment he left. Buying Robbo was the last straw for Clough who held a grudge against Taylor which he never resolved (although he eventually forgave Robbo and re-signed him at Forest for a handful of games in the 85/6 season).

The Thrill of it All

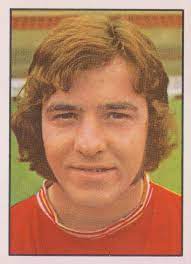

Forget about the end and relive the glory days. Dig out the greatest hits album again and give it another spin. You know each and every one of these hits by heart. Not just the goals, the crosses, the passes, the runs, and the rest of the magic with the ball. You know the two fists pumped in the air as he celebrates, skipping with the sheer enjoyment of his game. You know his cheeky grin as he runs back after scoring looking like he’s just played an hilarious trick on the school bully.

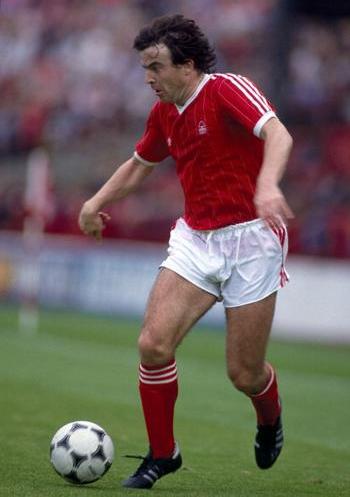

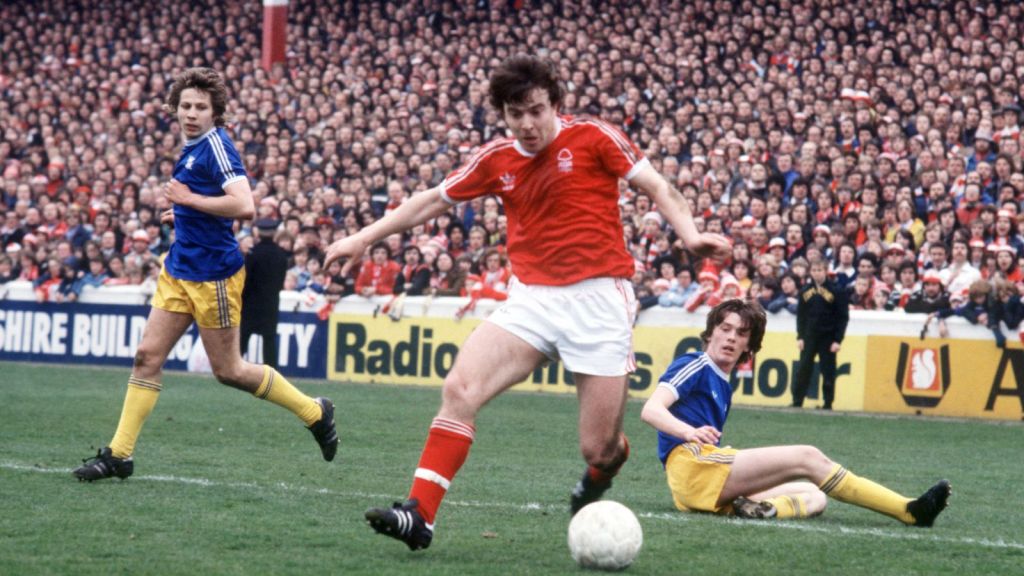

You look at the image on the cover. Robbo facing two defenders, the ball stuck to Robbo’s feet. The number 11 on the back of Robbo’s Garibaldi red shirt. His sleeves rolled up cos he means business. All three figures stationary, trapped in time, waiting. You study the picture and relish the memories it evokes. Then, before you can flip the cover over, he’s gone. He’s past the two defenders as if they were no more substantial than mist off the Trent and he’s onwards towards another goal.

That’s our Robbo. The greatest.

Numbers: Ken Smales & www.thecityground.com

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f3wpgC8Y1OA (c34 minutes). ↩︎

- The Joy of Six: football’s wing wizards | Football | The Guardian ↩︎

- Nottingham Forest 7-0 Chelsea 1991

Reds Hit SEVEN! 🤯 | Forest 7-0 Brighton & Hove Albion | Premier League Highlights ↩︎ - https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjwpOO-8-SOAxUmUUEAHXmqFHgQtwJ6BAgSEAI&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DAqhNqNtCinM&usg=AOvVaw2JXT8JjO6bhvxgojpawS4l&opi=89978449 ↩︎

- https://youtu.be/PAPFcY057r4?t=424 ↩︎