Dharma Punks

June 21 1977

This ain’t the garden of Eden

There ain’t no angels above

Things ain’t what they used to be

And this ain’t the summer of love

Blue Oyster Cult

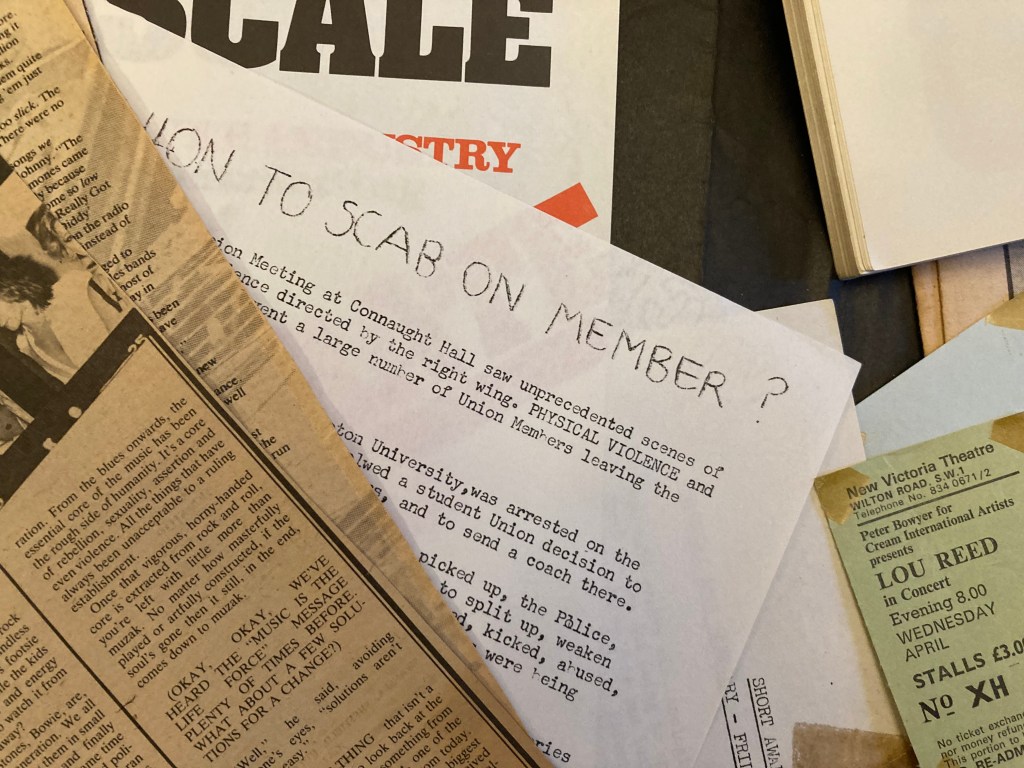

There was a Union meeting. This was on the Tuesday – the day after we’d got back from Viv’s sister’s. I went with Sonia as usual. And sat in the same space, just right of centre, close to the door. My true place in the enormous spectrum of student politics would have been to the left of centre, but that’s where the projector was, housed in an ugly lump of bricks and mortar, so accurate political statements weren’t possible. I would have to choose between the moderates, who wanted to build Jerusalem, but couldn’t get planning permission, and the extremists who wanted to pull down all the walls, but hadn’t come up with a follow up. Anyway, from where we were, you got a good view of both sides of the ‘house’ and you could get out quickly.

Tony Wise had put up this motion to send a coach to Grunwick’s. Wise was a hack, like almost everyone else that ever spoke at the meetings. It was like a soap opera where you knew all of the characters, Sedgewick, Walker, and Edwards on the right, Wise, Maynard, Jones, and Atkinson on the left. And you could pretty much guess what they were going to say – they’d all toe some variant of their particular party line, but shifted twenty or thirty degrees left on account of we were students and therefore more radical. And you’d also get the odd independent who’d join in, although it seemed like they’d try their hardest to avoid any party line, even if it meant coming over as totally inconsistent.

So we had to decide whether to send some folk over to Grunwick’s which was this film processing plant somewhere in London that had had a strike going for pretty much a year before it got trendy. Some of the folk that worked there had joined a Union and been fired for joining. So you had your various other unions lining up to join the picket line. It had started to get ugly, and the police were kicking lumps out of the pickets.

Like I say, it had got trendy, so everyone was talking about it at the Hall. One day I was enjoying tea and toast at the end of breakfast. This would have been the week before – maybe Tuesday or Wednesday. No – it must have been the Thursday, cos I had exams the other days. My last one was on Wednesday in the afternoon. Maybe it was Wednesday, because I always relax on the day of exams, I never do last minute cramming. Any way, it doesn’t matter, I was talking aimlessly with Bernie and this other geezer called Barleycorn, neither of whom would have had the same exams as me, being first years, when Mike and Lew came over. Have I told you about Mike? He was a serious radical, but I always liked him better than his other mates in the SWP. He was just a bit more clear and consistent in his beliefs, but unlike most of his comrades, sometimes appreciated that other folk had other ideas and had to be persuaded rather than just argued down. Sometimes, though, he could dig his heels in and rant as well as Rod and Neil. But Mike was the only one of that crew I ever saw stand up at the debating chamber. He was the only one who could really talk.

This morning he started by asking us, politely, to make sure we went to the debate and also to go up to London for the Picket, which he knew was inevitable.

And Barleycorn said: “You’re only going up to cause trouble”. Which would have been like a red rag to most bulls, but Mike took up the discussion in a more controlled way.

“No, we’re not. We’re going because we Believe in Something. Do you believe everyone has the Right to Join a Union?”

“Yes and the right not to,” said Barleycorn. That would be the answer Mike would know he’d get from everyone right of centre in those days. Bit of a cliché isn’t it – Physics student = Tory. Sorry. Anyhow, Mike would have heard it often, the closed shop being a discussion we’d had a couple of times, especially with respect to the Students’ Union which was, despite the effort of Monday Club regulars like Mr Sedgewick, still a closed shop.

“OK,” said Mike, taking up his case, “Imagine you’ve got a job somewhere packing boxes or whatever and you Join a Union and you get sacked for joining the union, what do you do?”

“You can’t prove they were sacked for joining the union,” says Barleycorn, trying to side-step the issue.

“Oh yes they were,” chorus Lew and Mike and Bernie. I knew that too, but I wasn’t that confident to just pick on Barleycorn like that. But then Lew and Bernie tried to prove they knew as much as Mike, so they both started telling the story, Lew vaguely, Bernie hurriedly.

I had a vague idea about what was going on at the time, from the papers, and I was trying to fill in the gaps. I’m a morning person, so my mind was fairly alive.

“What does Grunwick’s do anyway?” I asked. And that allowed Mike to start at the beginning.

“The name’s Grunwick.” He said. “No ‘s’. They develop films. They’re one of those cheap places that print your films in a couple of days at a third of the price of a place like Boots. The trouble is, they employ Cheap Immigrant Labour to handle the films and treat them like dirt. In the end, about a hundred of them Walked Out last summer because they were fed up with it.”

“So, what’s happening? Are they on strike for better conditions or were they sacked for joining a union or what?” I asked.

“They started the strike for Better Conditions – because the bosses pushed them around, threatened them with the sack, gave them compulsory overtime.” Said Mike “Then when they’d walked out they joined the union, then they got sacked. So it’s both.”

“They thought the immigrants would never strike,” said Lew “that’s why they employed them.”

“It’s got everything,” laughed Bernie. “Racism, union bashing, low wages, Victorian conditions, police brutality. That’s why it’s so good”. One of Bernie’s problems is that he gives the impression that things are a joke sometimes, but he was just as concerned about this as Mike.

“It’s not racist,” said Barleycorn, who, we were finding out, was a lot more informed than we expected. “I’ve seen the boss on TV – he’s Indian, just like the rest of them.” Which was partly true – dear old George Ward (nice Indian name that) was half Indian. But that didn’t mean that he didn’t exploit the Ugandan Asians that he hired. He paid them as little as he could and leant on them thinking that they’d be too scared of the sack given their low chances of finding work anywhere else. But even meek female immigrant labour cracks if you bend it enough.

“The point is,” says Mike, “they were fired a year ago, for trying to improve their conditions. The boss doesn’t want a union so he won’t take them back. They went to arbitration and ACAS said he should take them back, but he won’t. You see, the law just sits back in these cases and lets the bosses get away with it. It’s up to the Brothers now [even Mike couldn’t help slipping into unionese]. We’ve got to turn the screws and put pressure on Ward to comply. If we don’t do it, no-one else will [by ‘we’ he meant the workers of the world, which included all right-minded students]. We can’t afford to let this slip, otherwise every boss in the country will start kicking out anyone who’s joined a union.”

“It isn’t a question of causing trouble, Barleycorn,” said Bernie. They were good mates. They shared the odd lecture or too and got on quite well. “The Grunwick strike committee has asked for a mass picket, so it is our duty as union members to contribute.”

“Yeah,” said Lew, joining the argument. “The hippies had Vietnam, we’ve got Grunwick’s.”

“No ‘s’” said Mike.

Well, that’s how it ended that day, but Mike had another go at me after me and Annie had come back from our retreat.

“So Ned, what would you do?” He asked, picking up pretty near where he’d left off. “You’ve got a job that you hate. You could maybe get another, maybe not. Maybe you’d walk away and tell them to stuff it and take your chances. These folk, though, were more of a Community. They had a bit of backbone and a bit of Community Feeling, so they decided to fight for the sake of the group. They weren’t scabs, the ones that stayed at work, they were mates.

“So, imagine you and your mates are trying to persuade the boss to lighten up on the heavy handed management. You’ve tried talking to him, but it doesn’t work. So you get a union behind you. You try what they call ‘Collective Bargaining’. You get the union to try to sit down and sort stuff out. But that only makes matters worse because the boss is anti-union. But you’re in luck. Your friendly government has designed this industrial court or arbitration service to help you out. Their job is to suggest solutions. In an ideal world, they’d be able to impose solutions like a court of law, but you take what you can get. You ask them for help. And they say, sure you’re right, join a union, get the boss to back off on the overtime. But still the boss doesn’t listen.

“So, now what do you do? You can still walk away and let the next group of suckers who are more desperate than you, do the work. And they’ll stick at it until someone more desperate is found, and so on. Or you can try and Change Things. How? If the law’s against you, what do you do? How about passive resistance? Or passive obstruction? Block the factory gates, not let anyone in to work, not let any goods out. Or tell the world not to do business with the guy. Don’t send your film to him, or if you’re a lorry driver or a postman, don’t deliver anyone else’s films. But you’ll find that the cops move you on if you try blocking the gates. The Post Office will sack you if you decide not to cart the mail.

“And you wonder why there isn’t a law against what Ward is doing. We don’t allow kids down mines. We protect folk against dangerous machines. We surely should Raise the Standards of our Factories and Workshops.

“Welcome to the Working Class Struggle, Ned baby. The History of the Working Class has been one of Fighting for Basic Rights where the law has trailed behind.

“So, you Fight, Together. Your colleagues refuse to deliver mail to Grunwick. You line up outside the workshop and try to persuade people not to deal with them. I maybe sent my photos to them – how was I to know which EasyPrintTrueColourExpressPictures deal was right and which was wrong – nobody told me. But you have to try Ned, you have to try.

“And every step of the way, everything the workers tried, the courts said, “You can’t do that, it’s illegal”. Even though they’ve told Ward what he has to do, they don’t enforce that side. They only enforce the workers’ side. And when more and more folk turn up to express their support, more and more police get dragged in to keep them away. Even though the law says that Grunwick should change, all the justice in Britain, all the moral high grounds on earth can’t make Grunwick’s management toe the line.”

Like I said, old Mike could talk. He’s probably still in politics somewhere. And you know, all this was going down back in the seventies, when the Unions ran the country.

Anyway, back to the story. The debate me and Sonia went to that lunchtime followed this predictable line about union recognition and so forth, with the Tories fighting a losing battle, because the left had both morality and the law of the land on their side. But instead of arguing about whether the workers should be allowed to join a union, which is beyond dispute, they should have been arguing about whether to send a coach load of students down to sit on the picket line. And I looked at Sonia, and I looked at Jo who had also come and I wondered if they could see where the debate was going and I nearly stood up to throw my two pennies worth in, I nearly did.

See, what had been happening since that first day of the mass picket was brutal English fascism. We all knew it. Someone had decided that unless the mass picket was stopped, the strikers might win. So the police were told to get rid of the pickets by whatever means necessary. So they did. They’d arrest anyone who happened to be standing around, often quite violently. They’d push or kick people out of the way. It was like the Pistols’ boat trip all over again. Like Chelsea v Millwall. One rumble after another. We all knew that if we sent a coach of students up to Grunwick, some were going to get arrested or beaten up or both. It was inevitable. You lie in the sun, you get sunburnt. You go to Grunwick and you get arrested. Sure as night follows day. It’s not karma, it’s Pavlov’s frigging dog.

I wanted to say that while I agreed with the cause, we shouldn’t be sending anyone down, cause they’d only get arrested. And if a pack of students got arrested on union business, we’d have to pay their fines and such like and we’d have to put up with all the bad press and some wise guy local councillor trying to close the union down and all that crap.

And I thought I was the only one that saw this. So when the vote came, I thought I was being so clever by abstaining. And I got ribbed mercilessly by my old mates Rod and Mike, but I was so proud of myself for a few minutes. I argued with Bernie about it. He was up for going, but at that point, right there and then, I turned my back on the struggle.

See, it’s like this. You can have all the moral high ground on your side, but as soon as you slip, you fall so far that you lose. The other day I was playing football with Ally and Irish and Pete. We have this five-a-side league we play in every Monday night. [If you’re worried about my maths, just put Sammy the gooner in goal and you’ll be happy. Goalkeepers don’t count as footballers, even in five-a-side.] We had a chance of winning it, but we’d need to win the rest of our games. This last Monday we played a team we’d really hammered about a month ago, so we were expecting it to be easy. But they got an early goal (which was my fault I’m afraid) and after that they just defended like mad. Trouble was that they’d push and obstruct and trip and generally give us as much grief as possible. Now you’ve got to expect a bit of rough in these games, but Irish completely lost his rag. He’d be yelling at the ref. and then started going in high and elbowing and giving away free kicks. And Ally too, and Pete, who is normally so quiet, started joining in. And I was yelling for them all to try to wise up. Because we didn’t stand a chance of getting a goal back while those three were more concerned with kicking the opposition. So we lost the game. And that’s what happened at Grunwick. We were so right for so long. And then we tried to play it hard and ended up losing. We lost the moral high ground when the mass picketing started. We lost the moral high ground when they showed police blood on TV. And we lost the support we needed.

So I stood up and walked out of the debating chamber and away from the struggle.

And then, that Friday, early in the morning, a coach carrying twenty seven students left the Union building for North London. And two or three hours later, on that very same Friday morning, Annie and I managed to crawl out of bed and walk up the avenue to the start of the A33 to hitch up to London in order to see a bunch of overpaid musicians entertain themselves.

It was, of course, her idea, but having decided to turn my back on the brothers’ struggle, I wanted to do something equal and opposite to picketing. I’m like that. If I get hold of some principal, I’ll let it drag me right to the end of the earth. Most of the time I’m proud of what I’ve done. I can look back and say I’ve never done this or that because of principal. Like tactical voting. Or watching football on Sky. But on the other hand, I’ve cut me nose off three or four times to spite me face. Take this whole story. It wouldn’t have been possible had I gone to Nottingham University like I wanted to. But what happened was that they invited me up for the day and then forgot and there was no-one to show me round the department when I turned up. Probably a simple oversight for which I made them suffer by running away down to Southampton. Big deal. It cost me about 60 or 70 glorious games I would have seen had I spent my college years five miles from the ground instead of half the length of England.

So me and Annie hitched up to London, but our last ride took us only as far as Twickenham, so we have to walk for miles before we get to Viv’s place in Kew. I really like Viv’s place. It’s a flat her old dears converted for her above their house. She has an intercom on the door which opens onto the stairs. For years I wanted to live in a place with an intercom. It felt so exclusive. This time, though, we were worn out after the walk up the road past Kew Gardens. And we didn’t have much time to rest before we had to catch a tube over to Earls Court for the gig.

And, just in case you think otherwise, let me assure you that the gig was one of the worst I’ve been to. It was Genesis and they were crap. I expected that much. I’d got bored with them. The seats were crap. I expected that. I hate arena gigs. I swore I’d never go to Earls Court again after the Stones the previous summer. Even Annie thought it was a waste of time, so we left before the end. On the way back to Viv’s place I wrote a letter to the NME saying how bad everything was – the venue, the seats, the band. Maybe it was just too negative, though, too negative even for a punk rag, because they didn’t print it.

And then the next day we decided to go up to see me Dad because I’d realised I’d forgotten his birthday, which was about three or four weeks earlier. Yes, I know that’s pretty impressive, but I was distracted at the time. Wouldn’t you be? So, anyway, we tried to hitch north out of London. We got up right early to give us the whole day and then spent the whole of Saturday walking and tubing and bussing and arguing our way through Cricklewood, Golders Green, Brent, Willesden, and Neasden trying to find the M1. That was the day we nearly got a ride in a roller, but the driver changed his mind and sped off. Mind it was the nearest we got to a ride. In the end we went to Brent Cross and wandered around looking for something to buy the old man, because I realised we hadn’t got him anything for his birthday. Then we caught the tube back into town and got the 7pm train out of Euston. All day messing around in London and we just didn’t know where on earth we were going. And of course the irony is that we were wandering aimlessly round north London skirting the very film processing plant at Dollis Hill that was the centre of everyone else’s attention. We were lost while anyone with a life knew exactly where they were headed.

Then we met this guy on the train. You know how it is, you rush onto the train and scramble around trying to find a pair of seats that aren’t in a smoking carriage, and when you’ve settled down, only then do you notice who is sitting opposite you. Well, I was pretty knackered by then, but Annie decided to have a chat. This guy was our age, from somewhere on the Indian subcontinent, I never found out where exactly, and it turned out he was going up to see his Mam and Dad in Northampton and neither of them were well. And it was his old man’s birthday too! So we got talking and he told us how his Dad was really proud of his garden, but had been in bed for a couple of months so it had got really overgrown, at least according to what his Mam had told him, so he was going up as a birthday surprise and would spend the whole of the next day digging it over and such. Well, you can probably see this coming, but Annie volunteered us to go and help him. I said no, we should really see me Dad, but Annie was right and like I say, you should go where life takes you, so we got off at Northampton instead of going all the way to my old home. No really, and a good job we did too, cos it took the three of us until almost dark on the Sunday to fix it up, cut the grass, pull all of the weeds up, and so on, sleeping on the floor on the Sat’day night, cos although it wasn’t too big a place, it was very, very overgrown. More like two years of neglect, not two months. And between you and me, it can’t ever have looked as good as it did then.

And the other thing was that Annie made the most wonderful meal on the Saturday even though it was late. It was a western meal, all pasta and tomato sauce and vegetables and herbs that we bought in a corner store that was still open as we walked back from the station. The old couple were really flattered to be treated to a dinner in their own homes. We offered them the bottle of wine that I’d bought for me Dad’s birthday from Brent Cross, it being the only thing we could find that I thought he might like, but they said no, so me and Annie tried to finish it. It was sweet white which is the only wine me Dad likes. It was awful. I don’t think my Dad ever got a present that year.