Dharma Punks

June 2 1977

Leave your cares behind

Come with us and find

The pleasures of a journey

to the centre of the mind

The Amboy Dukes

Bernie knocks on my door. At first I don’t hear him, his knocking is uncharacteristically soft. It is late, past 11 and I’ve been revising too much. These late night calls are getting to be a habit. The previous night it was Annie. She came round just as it was getting dark and suggested we go for a walk down to the Common. Walk with Annie or revise? It’s a no brainer.

We go down to Burgess Road, me and Annie, and then cut into the woods, off the paths, near where Chris had taken me that time the month before. The night had started cloudy and was that dark orange grey you get in the city. Enough of a glow to see. I could make out her face, the surroundings, where we were going. Annie grabbed my hand and said: “Come here, Tutti. I want to show you something.”

Tutti was what she called me when she was being most affectionate. Sometimes she called me Ned. Sometimes she called me Riff. Mostly she called me Tutti. I thought it was German. Annie and Jo had a habit of using German words every so often. Stuff from out of their pretentious books like Hermann Hesse and Thomas Mann. “Oder”, “Mensch”, und so weiter. What is it with me and language students? Annie and Jo did German. Sonia and Mary did Spanish. Helen and Debbie did English. Mind Vic did Environmental Sciences and Elsa did biochem or something, so it’s not all one way traffic.

Anyway, Annie grabbed me, “Look at me,” she said. We were in a bit of a gap between the trees.

“Now look at the sky over my right shoulder… wait… there.”

As I looked up, the clouds brightened, becoming lighter and whiter and then parted so that this beautiful big moon burst forth smiling like Helen when Chris enters the room. Annie leant on my shoulder as the moon bathed the world in a silvery light.

“How d’you do that? How did you get the full moon to start shining?” I asked.

“Away, you wee dose,” she said. “It wasn’t me. It was the wind did it. I thought you were a scientist. I thought you knew these things. All you have to do is watch the clouds and work out the rest.”

So, no actually, I haven’t been revising too much this week. I’ve only just started today. What I mean is that I’ve been reading about Australopithecus, Dryopithecus, Zinjanthropus, and their mates for the past hour and my mind is warped. I figured I knew all the geology I needed to know, so I should concentrate on my other subjects. And after studying archaeology all night, I know what it is that turns these archaeologists crazy. I’d thought it was the mushrooms.

So Bernie coming round is just the distraction I need. He has me put me shoes on and drags me downstairs where Helen and Chris are waiting with the mighty Herald. It looks beautiful, like a pearl, under the moon’s bright light.

“We’re going to Stonehenge,” Helen tells me. I’m invited.

“Can I bring Annie?” I ask before I realise the car only seats four.

“Sure,” says Chris, which means he’ll share some of the blame I’ll get for the cramped conditions going and coming back.

Annie has been banished to her room tonight so that I can make a start on the archaeology revision. She doesn’t understand, cos all she has to do is turn up for a couple of exams at the end of her three years, speak German or French for half an hour and read a book and they’ll give her a degree. It’s different for geologists. They watch folk like me every day for three years. Every exam counts, even the meaningless ones like archaeology. So if you can’t tell your Australopithecus afarensis from your Australopithecus africanus, even without their full dental records, you’re out on your ear, babe.

So we drive over to Glen and I rush up to her room, peek round the door, and see her gently gaze over from the bed where she wasn’t yet sleeping and smile. I explain the plot as she pulls on some jeans. But when we get into the car, she starts to wind me up by asking if I can discuss the role of the Danube valley in the spread of copper metallurgy to northern and western Europe. So, I begin to think she may have spent the evening under the influence of Aggie Parker, also known as Viv the archaeologist and resident lunatic of Glen Eyre. And it’s lucky she’s not still with Annie or it would have been six of us in the Herald. Tense.

We’re all in the car and the first thing Bernie says is “Do you know the way?” He likes to think that, just because he’s local, he is the only person who knows the way. Well, local, in that he’s from Portsmouth. So he tells Chris to head down Winchester Road, go over to Totton, and then get on the A36. The rest of us, me, Annie, and Helen, all know that Chris knows the way. But the surprise is that Bernie doesn’t.

So we head down Winchester Road. I used to have to cycle that road in my first year, because I’d been stuck out in digs. I thought no-one else even knew about that part of town. People lived in Shirley, Bassett, Bitterne, Portswood, or even Highfield, but never Millbrook. I almost suggested that we drove past the old place, but it was such a lonely, quiet backwater and I felt I didn’t want to share my memories. Annie touched my hand as if she’d heard what I was thinking. And then Bernie said:

“We’ll need some goodies for the journey, we should stop and buy something.” Of course back then, most places shut up at nine or ten at night. There wasn’t a prayer that we’d find anywhere open. When we’d past a closed up petrol station and a closed up corner shop, Bernie started to panic.

“Riff, lad, have you got anything to eat back at your room?” Of course I hadn’t, just biscuits and tea.

“Well we could take a packet of biscuits. That would be OK wouldn’t it?” He asked.

Helen enquired if he thought about anything other than his belly. We all knew Bernie was capable of thinking about lots of things other than his belly, in fact he was capable of talking about lots of things, all in the same sentence, and sometimes making sense about them, but the girls wanted to wind him up. Annie said she had some fruit in her room, which was true, sometimes I’d share an orange or a banana with her, but she said she couldn’t be sure if she’d got it last year or the year before. However this wasn’t a joke for Bernie.

“Turn round Chris,” he demanded. If you know Chris, you know he’ll do it if you ask him, so he turned round. We’d got as far as the Redbridge roundabout – only about five or ten minutes drive. We went back to Chamberlain, and I fetched my biscuits – one and a half packets worth. Annie fetched a bag of fruit and Helen asked, with a forgiving smile like a mother has, if Bernie was happy now. He was, so we set off again, down Winchester Road, past Millbrook and out towards that bridge over the Test. I got the same echo of loneliness passing near my old haunt and got the same warm touch from Annie. I’d told her about my first year, but I couldn’t quite remember the conversation in which I’d told her exactly how I’d felt. The more I thought about it the more I thought she must be inside reading my mind, so I pressed up closer to her, which isn’t hard when you’re the middle one of three sitting in the back of a Triumph Herald.

“What do you know about Stonehenge then Riff?” asked Bernie.

“Not much, I’ll tell you,” I said with what I thought was modesty.

“You not doing archaeology then?” All geologists did archaeology. It was supposed to be one of the easier options like Aspects of Environmental Sciences. Well if the university forces you to take half a dozen subjects from outside your degree, then there’s bound to be a market in courses for dossers. The geology department was no different. It was trying to sell a rocks for eejits course. Me and Percy tried to sign up for it in our first year in an attempt to get some easy credit, but they obviously weren’t that desperate, so they bounced us.

“Oh yeah,” I said “It’s just that I haven’t figured out what its all about yet. What I do know is that these dudes legged it over to Wales and were sold some cheap rock which they put out in their back yard in the same way you’d put out gnomes if you lived over in Shirley. Apparently they shipped them down the Severn.”

“The other theory is that they’re glacial?” asked Helen. We’d covered that too, in one of the lectures I’d been to, but I was a little disappointed Helen knew something that had slipped my mind, what with her being an English student. Anyway, this allowed Bernie to tell us about the ice age.

“You’d expect the ice to bring stuff from the north, not the west,” said Bernie.

“I’d expect the ice to do all the work for me if I was an ancient Brit,” Annie said. “I wouldn’t shift stuff I couldn’t fit in my pocket.”

“They put them on barges and shipped them down the river,” Bernie told us. It seemed they all knew more about these bleeding bluestones than I did. I asked Chris what he thought.

“It doesn’t matter where they came from,” he said. “Whatever happened, it took an amazing amount of co-ordination, skill, and commitment to build the place, so it must have been important.”

It was true. So, the bluestones came from Wales. But the main structure is made up of even bigger stones. And even though they came from just twenty miles away, it still took a load of trouble to shift them. More trouble than the Stranglers had put into the lyrics on their album anyway. And all of this work posed a real problem for twentieth century man who thought he was the only one who had the technology to do anything spectacular. Hence the UFO stories and the hand of god stuff, but no-one in the car was going to bring those idiot theories up.

“So what’s it for then?” I asked, feeling the least knowledgeable of the bunch, despite the fact that I was the one who’d been revising archaeology that evening.

“It’s a calendar,” said Annie. “You could use it to see when the Pistol’s next single is out.”

Bernie enjoyed that one, although I expect it went over Chris and Helen’s head.

“That’s right Riff,” he said. “I thought you were the hip young punk about town. So how come you forgot the day that God Save the Queen was released.”

Yes, I did think I was the hip young punk about town. It was going to take me a long time to live that down.

“She made you a moron,” sang Bernie. Unfortunately Chris didn’t have a radio in his wagon, so we had to put up with a couple more verses from Bernie’s mighty tonsils. Then when he tried to draw breath for another onslaught, Chris interrupted him and steered the conversation back to Stonehenge.

“Most of these stone circles started out as models of the world. The folk that made them thought the world stretched as far as the horizon. They’d look around them and see various hills or whatever in the distance and think that there’d be nothing on the other side. Or if they did think there was anything on the other side, they didn’t really think it was part of their world. So they built a circle, stood inside it, and said this is all there is. Sometimes they made the circle look like how they saw the horizon.”

“How’s that?” I asked.

“Stonehenge has got stones that are flat on top, but other circles are different. The stones look natural, but if you go to say, Castlerigg, up in the Lakes, and stand in the middle, you can see that they’ve shaped some of the stones like the hills around.”

“Surely that’s just chance.”

“No” said Chris, not forcefully, but calmly and with confidence, so I believed him. Well wouldn’t you match the stones if you were putting up a circle? To make it look better.

“So, Stonehenge and all these other places are like temples to their worlds?” asked Annie. “You could make offerings or whatever if you wanted to improve your lot.”

“Not only that” said Chris. “You go inside Stonehenge and you start to awake to your world. It’s a bit like meditation.”

“But they’re observatories as well,” I added. Everyone knows that Stonehenge lines up with the midsummer sunrise or sunset or whatever.

“Lot of trouble to go to to make a calendar isn’t it?” said Bernie. “All you need is a few sticks.” I guess we’ve all made sundials, and you wouldn’t need to do a lot more to work out something to track a whole year.

“What have most of the important buildings in the world got to do with?” asked Chris and then he answered himself. “Death and rebirth.”

“What, even the Chrysler Building?” I asked. That’s always been one of my favourite buildings.

“Actually I was thinking about religious buildings like churches and temples. I think they outweigh skyscrapers.”

And Helen said: “So it isn’t so much about knowing when it’s midwinter or midsummer, or new moon, or whatever. It’s about recognising the significance of them, making sure you acknowledge how important they are. It’s just like you and your wall, Ned. You’ve got all of those posters and stuff. You spend time on the important things.”

And I let my mind imagine year upon year passing by Stonehenge. Suns rising and setting, moons waxing and waning, souls dying and being born again. All of these cycles forming interlocking and interconnecting circles over Salisbury plain as part of some giant clockworks.

†

“Riff’s gonna write a book” says Bernie, apropos of nothing in particular. Maybe it was an inner monologue he’d been having that had finally burst to the surface. “The Tao of Riffy.”

“Tao?” I asked

“Yes, it means the way,” he responded. “How to do stuff. “Or the Tibetan Book of the Ned. Or Zen and the Art of Palaeomagnetism.” He was on a roll.

“Zen in the Art of Palaeomag – I like that,” I said.

“It’s ‘and’ not ‘in’,” says Bernie. “It’s Zen AND the art …”.

“Could be either,” says Chris. “Zen in the Art of Flower Arrangement. Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Those little words are important. Which one you choose matters. It completely changes the meaning of whatever you want to say. ‘In’ means you are inside. ‘And’ means you are outside. Like ‘The’ and ‘A’. Are you the Ned or just any old Ned?”

“So what’s it going to be, Riff? Asked Bernie. “How are you going to spread your philosophy on music, life, and everything?”

“You don’t have to write a book,” says Annie. “You should just be. That’s the best way to teach. By being. Be yourself. Be your philosophy. Actions not words. Be the best yourself you can be. ”

“She’s right,” says Chris. “Think about it, Ned. And you Bernie. What have you read that influences you, apart from the NME? But think about who influences you. Who has changed you.” I didn’t need to think. I squeezed Annie’s hand to let her know that I already new the answer.

“Annie’s right. I hate writing. I hate essays and exams and stuff. I ain’t never gonna write nuffink.”

But you never know. Keep your eyes open for ‘Zen in the Art of Palaeomagnetism’ by Edward E Wood.

†

Chris pulled over. We were in a small village.

“This isn’t Stonehenge,” said Bernie.

“I know,” said Chris. “This is Godshill. You wanted to come here.” But still Bernie looked puzzled.

We all got out. We were next to a school. Chris led us round the back and across a field. I was a little nervous because it seemed as if we were trespassing and we were pretty obvious in the moonlight, but Chris and Helen walked on confidently, so we followed. We were on the side of the valley walking more or less along a contour. On the right the slope up was gentle enough for it to have been cultivated into fields. On the left, the ground dipped more rapidly toward the river and was wooded. Then we stopped.

“This is it,” said Chris. He’d been here before.

“What?” asked Bernie?

“You tell me. You wanted to come here.” Chris said again. Then Bernie remembered.

“This is an Iron Age fort.” Chris explained. In the moonlight falling through the trees you could see a large mound forming a circle, which would have been the edge of the fort. Before the wood grew, you’d have got a great view of the valley.

“It’s a ley line,” said Bernie. “There’s an earth line from here all the way to Stonehenge. I told Chris we should come here.” His scientific upbringing had deserted him. It got worse. “Aliens use it all the time. If we stick around long enough, we’ll see a U.F.O.”

“You haven’t been listening, have you?” said Helen. “You are supposed to be looking inside, not outside.”

Annie, meanwhile put her arms around me and whispered that she felt like she was on another planet whenever I was around, which was only partly tongue in cheek, so I gave her a long warm kiss.

Chris and Helen found a place to sit and meditate while Bernie wandered off to explore. Annie and I just sat and talked, mostly about nothing, or enjoyed the eerie light of the moon and the echoing silence.

Later I asked Chris about ley lines. He was cool. He said he thought some were designed to be straight, the way you’d line up stuff you were building just to make it neat; some were chance; and some were even following lines in the earth. Real lines, he said, like you geologists learn about. Maybe, though if anyone had a habit of building on faultlines, you wouldn’t expect them to stick around long.

Anyway, we got back to the car and Chris drove down the hill and then turned onto the Salisbury road. But suddenly he swerved as if to miss something and hit the kerb. We got out, me, Annie, and Bernie from the back, Helen from the front. It happened quickly and none of us were hurt, just a little shocked. I’d done it myself back at home in me Mam’s car the previous summer, giving too many people a lift and not taking care. I’d lost control cos of the weight as I’d gone round a corner and tried to do tricks. All of a sudden the car had decided to go up the kerb and that was that. I felt so embarrassed. But the first thing Helen said was “It was OK Chris, you didn’t hit it.” and then we found out that a rabbit had run on the road and Chris had swung the wheel round to avoid it, but swung too far and had gone off the road. And now we had a near side flat tyre. So we get out the spare and fix it. Actually Chris and Helen do the work, because they know what they are doing, the rest of us just watch.

You know, it’s strange. I only then realised why I didn’t think it was strange those two having a car. See, they’re like a family. They’re not students like me and Bernie and Annie. They’ve made the transition to being grown up. They live in their own house and drive their own car and live their own lives. The rest of us live by hall meals and lectures.

And at last, the car is fixed and Chris and Helen are congratulating themselves on having missed out on a year’s bad karma by not squashing the bunny.

To be honest, I’d lost all track of time by then. It was still night, but not dark, on account of the full moon, so we were existing in a silvery dreamworld. Everything was slightly unreal, slightly Alice in Wonderland. And just like Alice, you deal with the unusual as if it happened every day. So I wasn’t surprised when we spotted someone walking by the road as we drove through Salisbury and I wasn’t surprised when he stuck his thumb out as we passed, and I certainly wasn’t surprised when Chris pulled over and got out to talk to him. And I knew for sure that it had to be no-one other than my new mate Rich from Oxford.

So we stopped in the shadow of that great majestic spire. Helen opened up the boot of the Herald and pulled out a couple of bags and shared out the contents – sandwiches, apples, oranges, bananas, and a few bars of chocolate. Chris invited Rich to join us; you could tell that they’d hit it off immediately. Maybe they’d known each other in previous lives.

We were all looking at Bernie, waiting for him to remember the fuss he’d caused about grabbing some food as we were leaving Southampton. He had a mouthful of grub when his face changed as he realised that Helen and Chris had packed up some grub for the trip, proper grub like sandwiches, but hadn’t let on and had done all of the chasing around to humour him. He looked at Chris and, wiping the crumbs from his lips, asked why Chris had let him waste everyone’s time at the beginning of the trip.

“Because you wanted to do it,” was all Chris said. Bernie just sat on the bonnet and tried to think why someone with a car full of food, would turn round and go back three or four miles to fetch a packet and a half of biscuits just because some guy was throwing a wobbly.

Meanwhile, Helen was telling us about one of the times she had come to Stonehenge late at night. Apparently she’d tripped up on some wire and all of these searchlights had come on.

“Kind of spoils it, doesn’t it,” said Rich. He sounded like the old hand I knew him to be. “You need to be there in natural light. One of the most amazing sites is strolling down the avenue toward Stonehenge at dusk on mid-winters day and seeing the sun set in front of you. You can just imagine the wonder that filled the minds of the guys that built it and lived it. You can step back and follow their thoughts. Experience what they felt.”

The he asked us whether we were going to Old Sarum first. “Are you coming up the ley from Clearbury?”

Bernie laughed. “They don’t believe in it,” he said.

“Oh, they exist, man” Rich told us. “There just aren’t as many as people make out. Trouble is that people look for them with maps. The guys that built Clearbury and Old Sarum didn’t have maps. They just had eyes. That’s what you use to find leys. Your eyes. Just head out into the country and whenever you find something that lines up, that’s your ley. And that’s all it is. A group of things that line up. It isn’t mystical. It’s just what you see.”

“Ah, but you’re wrong,” said Helen. “What you see is mystical. It may not be associated with aliens and magic and stuff. It may only arise from inside someone’s head, but surely that’s the most mystical place there is.”

“Yep, you’re right,” he acknowledged. And then he said, “Shall we go. It’s starting to get light.” He clapped his hands to speed us up. Hearing this, Chris smiled and quoted one of his poets.

“Summer Moon

Clapping hands

I herald dawn”

“You beat me to it” said Rich, graciously. “How about:

“Summer Moon

silverly lights

my inner soul”

Helen:

“Sunlight’s fingers

Inside the circle

looking out”

Yes. We are always inside the circle, looking out.

“I don’t know about you guys, but I need some sleep,” said Bernie.

Well, I didn’t think there’d be any chance of sleep, because the six of us crammed into the Herald and drove the last five miles of our journey. Not to Stonehenge, but to a place the other side of it, so, Chris said, we could approach Stonehenge, on foot, down the avenue. The front door, he explained.

Bernie had fallen asleep by the time we got there, so we left him in the car. Rich, Chris, Helen, Annie, and I walked toward the monument, small, but clear, in the distance, as the sky grew light.

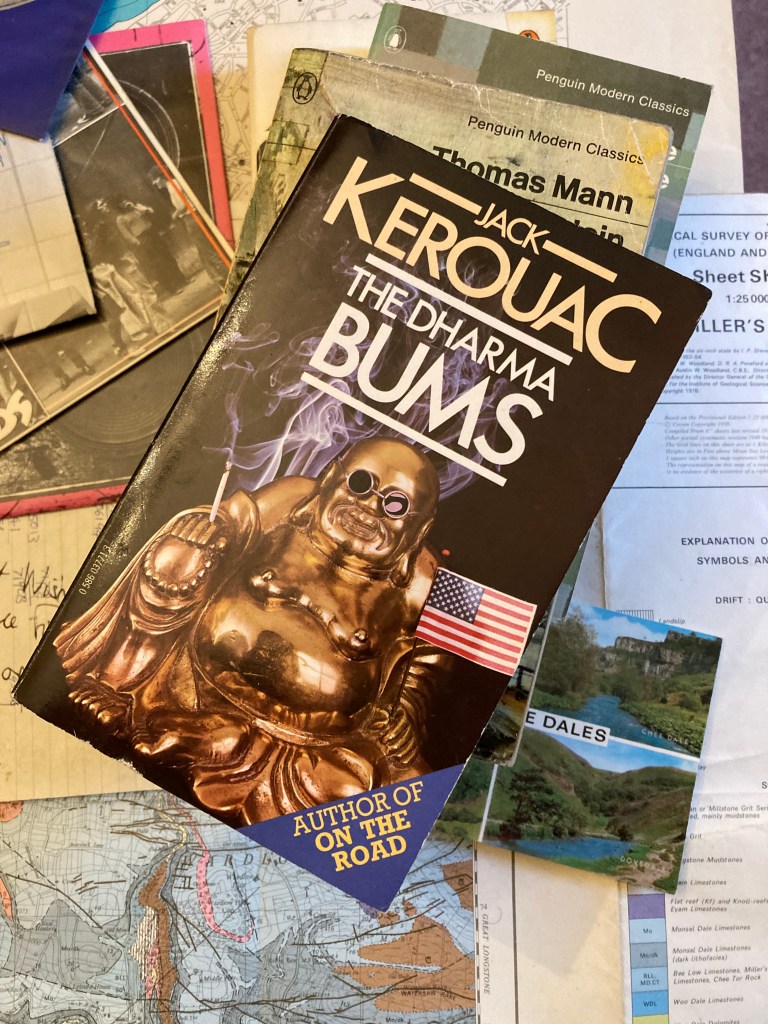

Rich pulled a beat-up paperback out of his pocket and thumbed through it. A different beat-up paperback from the one he was reading when I’d met him. A beat-up paperback with a fat buddha on the front. I recognised the respect he showed for the words in the book, if not the pages themselves. I recognised the look on his face. The need to frame a moment. He wanted to say something, but he wanted to get it right. Chris said something about Zen Lunatics and poetry, but Rich held up his hand. “This moment is so perfect, I want to get it exact.” And then he read.

“A world full of rucksack wanderers, Dharma Bums, refusing to subscribe to the general demand that they consume production and therefore have to work for the privilege of consuming, all that crap they didn’t really want anyway such as refrigerators, TV sets, cars, at least new fancy cars, certain hair oils and deodorants and general junk you finally always see a week later in the garbage anyway, all of them imprisoned in a system of work, produce, consume, work, produce, consume, I see a vision of a great rucksack revolution thousands or even millions of young [and here he hesitated slightly as he quickly changed the original from ‘Americans’] … young Brits wandering around with rucksacks, going up to mountains to pray, making children laugh and old men glad, making young girls happy and old girls happier, all of ‘em Zen Lunatics who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads for no reason and also by being kind and also by strange unexpected acts keep giving visions of eternal freedom to everybody and to all living creatures.”

And with that, Rich grabbed Chris and Helen by the hands and the three of them ran across the field toward the monument whooping and yelling. I looked back at Annie who smiled her broad wide warming smile. Then I turned back the way we were heading and looked toward the stones. I could make out the inner group of trilithons standing tall and imagined them to be the brudders surrounded by an admiring audience.

“Don’t they look like the Ramones from this distance?” I asked her.

“Don’t take this Dharma Punk stuff too seriously,” she said and put her arm in mine. As we walked down the avenue with the sun rising behind our backs you could see our long early morning shadows, veering slightly off course to the right, but still staggering vaguely towards the magical circle in front of us.