Dharma Punks

Early July 1977

All surroundings are evolving

In the stream that clears your head

13th Floor Elevators

I’d got a cosy little room at the pub. There was a small window facing the river and an old table in front of the window so I could sit and watch time pass by. On the wall were a few Chinese or Japanese pictures. A little story of a guy chasing a cow. I guess someone must have bought them in an old junk shop and put them up. One of them was missing. There was a gap in the row and a hole where the nail had been. And there was an old bookcase with lots of old paperbacks. They’d all been read, some often, and many were on that really thin paperback that the oldest paperbacks were printed on, so they were quite delicate. They’d been treasured once, but now it looked like they’d been stuffed up in the top room out of the way, so no-one would have to see them again.

I read all sorts of things while I stayed there. Sometimes I’d go and sit outside by the river and read by the last of the sunlight, sometimes I’d read in my room. Even after I’d moved out, I still came by and borrowed a book or two. They didn’t mind, so long as I read by the river, and didn’t take the book away with me. That’s where I found out about folk like Orwell and Huxley and all that jazz. All of the obvious stuff really, but I’d never read before. Strange that when we went back to Southampton, Annie would start getting me into European authors like Kafka and Camus. The folk she had to read from her course. And Thomas Mann. She hated him.

I wrote to Annie a lot from that room. Long letters to fill the quietness. Rambling letters without any structure, just telling her what I’d done that day. She didn’t write me letters in exchange, but she sent me cards, sometimes with messages on like ‘You should be here’. Sometimes a butterfly, sometimes just the letter A in her own unique style, knowing that merely the sight of it would cheer me up. After I’d moved out I still used to pick up my mail there. I’d go in, order half a Stella, and the landlady would give me Annie’s latest card and say, “Look after her. She really loves you.”

Any way, I had a good kip on that first night. When I woke up, there wasn’t a sound in the place – all I could hear wash the rush of the river. I went downstairs into the bar, but there was no-one there either. Stepping out of the front door, I saw this old guy sitting at a picnic table. He turned and got up.

“You’ll be wanting some breakfast,” he said. “You’ll not get any such like in the bar.”

He took me to his cottage just up the road where his wife had brewed up a mean pot and explained that no-one lived at the pub anymore, but that the landlady turned up just before lunch after she’d finished the farmwork. He pointed along the road to Tideswell showing me the approximate direction of the farm she worked on.

After tea and toast, he suggested we both go over to Preistcliffe, because there was someone I should meet. I almost said I didn’t think he would be up to climbing up the hill as I’d done the previous day. He looked too old to be hill walking, but it turned out that he was just as fit as me, maybe fitter. We followed the same route I’d taken: over the river Wye, and up towards the quarry. Halfway up, he pointed back across the valley to where Monks Dale ran away from us. Its small stream joined our river not far from the Traveller’s, but from this distance I could hardly make out its course. I followed his directions to make out a farm on the east side of the dale.

“I don’t suppose you care whether that’s the farm she works at or not,” he said, referring to the old dear who pulled the pints at the pub, “but you should care about what causes the slope to change all of a sudden, there behind the farm, and over there on Knotlow” and here he pointed at a comical little hill across the valley to our left. “That’s toadstone.”

Of course I hadn’t heard about toadstone in Southampton, but I made a note in my notebook in case it came in useful. And before I’d finished, he’d set off again and I had to run to catch up.

On the crest of Preistcliffe Lees, we stopped to admire the view. You know that stage-diving that you get at some gigs. Where people from the band or the audience dive off stage or just fall off stage and let the audience catch them. Me and Bernie saw the singer from some band do it around then. Not a punk band mind, it must have been a bit later, maybe when the Rich Kids came to Glen or something. Anyway, that’s what I felt like doing that day. When I get to the tops of hills and the like, I sometimes feel like diving off because I’m sure I would float off and not come down.

“It always gets me here – that view,” said my companion, his hand tapping his chest. I didn’t think he’d understand about the stage diving so I didn’t tell him what I was thinking.

So we moved on toward Priestcliffe. Then across a field, we spotted a farmer. This apparently was who we’d come to see, so we waited by the wall as he came towards us. After a quick chat, the farmer walked back to the middle of his field, pulled up a small flower, and came back.

“This is no good for my animals, but you’ll love it,” he said, showing me this small thin plant with delicate white flowers. “It’s leadwort, put some in your pocket”.

“So, now you know all you need to know,” said my companion as we walked over to the other route down past the quarry. “You can find all of the toadstone by looking at the valley sides and hills, but if you want to do really well, just look for that white plant, and it’ll tell you were the lead is. Just don’t tell that grumpy old bugger at Hall Farm, ‘cause he’ll think you’re going to dig up his fields.”

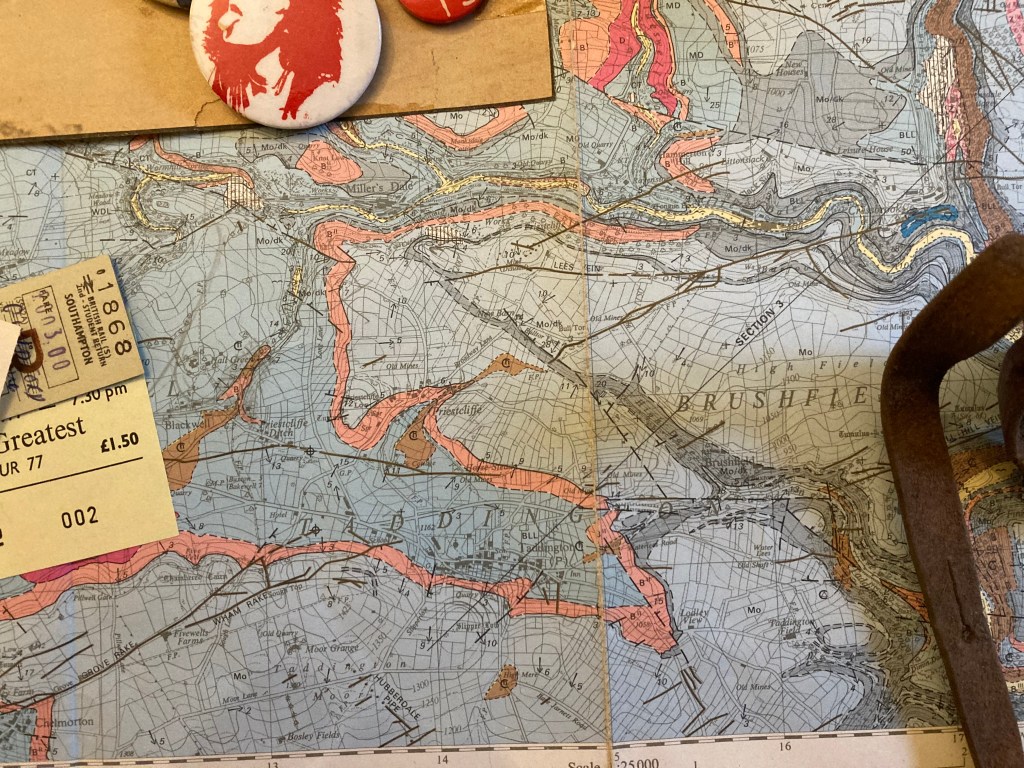

Well, I never was any good at botany, so I didn’t find any of the mineral veins, but he was right about the toadstone. Once I’d been over to Knotlow and worked out he was talking about lava, it was pretty easy to sit up on top of Miller’s Dale quarry, look over at the shape of the hills, and mark on my map all the places that weren’t limestone.