All the Young Dudes

Staying back in your memory are the movies in the past. The important stuff that stays in your brain, replaying on the screen in your head. David Bowie singing Starman on Top of the Pops. Me and Rosie Jones walking home from school, holding hands. Duncan McKenzie raising his right arm to celebrate yet another City Ground goal. 1972, 1973, 1974. They were a wonderful time to be alive, the early 70s, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Rosie Jones wore a bright red school uniform. She was skinny and shy. Her shock of dark brown hair that never behaved framed her sweet, innocent face. If she caught you looking at her she’d look away but then a smile would break out on her face like the sun sneaking out from behind the clouds.

Duncan McKenzie wore a long-sleeved red shirt with red cuffs and a red wing collar. An all red shirt with two stags on the chest. When he scored, he’d raise his right arm in acknowledgement as a grin broke out on his face like a schoolboy who’s just snaffled the last slice of chocolate cake. He was skinny and far from shy. He had the precious ability to excel at the game of football and the even more precious ability to be able to enjoy the game of life whatever he did. He played for fun. Always with a smile on his face. He looked like he would come second best in an argument with a dormouse. But boy, could he play… His appearance was misleading: he was strong and tremendously athletic. He could fly. He could jump over cars for bets and he could jump over centre halves for laughs. He could throw a golf ball the length of a football pitch and he could throw a dummy so outrageous he’d dump his full back on the turf or put him in the stand next to the golf ball. He’d go on long mazy runs all over the pitch like a six-year old chasing a butterfly. Sometimes he’d end up nowhere, but, more often, he’d open up a gap and create something. (And in these days of 20% possession, what wouldn’t we give for someone who could just keep the ball regardless of where he was going?) He’d skate over the pitch. He’d dribble his way through any defence. He’d beat his man and then go back and beat him again, just for fun. He could lick ’em by smiling. He could leave ’em to hang. And he scored goals for us. 41 goals in 111 league appearances … 5 in his 13 FA & League Cup games … and 9 from 15 County Cup and other games.

The Football League was full of entertainers back in those days. Players to get you excited. Alan Hudson. Tony Currie. Rodney Marsh. Frank Worthington. Stan Bowles. Players to set your heart racing. Players too good to play for England. And the best of the mavericks was Duncan McKenzie.

There’s a story about his first year at Forest. The lads have come back from training and McKenzie’s boasting about his golf ball throwing ability. He has a wager with one of the old pros: I can throw the ball further than you can hit it with a golf club. So they walk out onto the City Ground pitch and take up their positions outside the tunnel. McKenzie takes a golf ball in his right hand and launches it over the old East Stand. The old pro takes his golf club, swings, and drives the ball hard and high, but it fails to clear the stand and clatters against the roof, causing a piece of the roofing to break off and fall to the ground.

“Double or quits”, says the pro and swings again. This time his ball sails over the stand. McKenzie takes another ball in his left hand and this time clears the stand with a left arm throw. McKenzie thinks he’s won the wager, but the old pro doesn’t pay up. They’re still arguing the following morning when they turn up for training again. Only this time they’re called into the bosses office and presented with a bill from the owners of the property behind the East Stand who’ve had their windows broken by flying golf balls.

McKenzie was born in Grimsby and was playing in Cleethorpes when spotted by Forest. He signed for Johnny Carey’s Reds in July 1968 just after his 18th birthday, but when Carey was replaced by Matt Gillies, McKenzie found himself out of favour. He played once in the 69/70 season and made 5 substitute appearances in 70/71 before being shipped off to Mansfield on loan. On his return in April 1970, he scored twice in a 3-1 victory against Man City at Maine Road but was immediately dropped, only getting his place back when striker Neil Martin was injured. Not an auspicious start.

I should have been a Villa fan. I was born and brought up down the A38 towards Birmingham. Villa country. Many of the lads at school were Villa. A few Wolves and West Brom with one or two glory hunters who supported Leeds or Liverpool plus the odd Walsall supporter and the even odder Coventry fan. I pestered me Grandad to take me to a game but when he took me to Villa Park, I fell in love with the away team, Ian Moore, Joe Baker, et al. That wonderful white away shirt we wore back then. Anyone would fall in love with them.

By autumn 1971, I could travel to games on me own. It was a bit of a marathon: leave home before 10, catch the slow bus through the villages to Burton. Train to Derby and then another train to Nottingham Midland. I soon fell in with a handful of youths from near Burton. 14 and 15 year-olds. There was a lad called Les who I got on with – he went to the same school, even though he lived miles away. A couple of the others were little thugiwugs though, if we’re being honest. Mind, I learned a lot by watching them and listening to them. How to keep out of trouble at games. Places to avoid before and after the match. When to keep my head down. When to leave ‘em and viddy the game on me oddy knocky.

“Righty Right brothers, what’s it going to be then?” says Les when we get off the train in his own unique mix of Nadsat and East Staffordshire slang. We get to Nottingham ridiculously early because the trains don’t go so often and we’ve got time to kill.

What’s it going to be then, eh? We could go into a caff on Arkwright Street near the ground for some chai or some chips and a gravy pie. Arkwright Street is all shops back then. We walk down the street like we own it.

Or we could go to the Queens Hotel for a drink. Les and his droogs show me how to get served. But, being only fourteen, I can hardly manage more than half a pint.

Or we could hang out in the club shop – just a portakabin in the Main Stand car park – and then skulk in the old alley between the Main Stand car park to the Trent End where, one afternoon, I scrawled my name on the bricks – 40 years before you could pay for the privilege of having your name on the Trent End wall.

Or, if it was sunny enough, we could sit on the banks of the Trent and chat. They’d talk about music: Otis Redding, Doris Duke, Donnie Elbert, Robert Knight. Some of the names went over my head, but I learned I could gain credibility by repeating them to the young malchicks at school. We were tribal back then. If you were into football, you had to be into soul, Motown, ska, and maybe Bowie. If you weren’t into football, you had to listen to Sabbath, Purple, and Quo. So I was desperate to discover new soul names to drop.

I was soon dressing like the rest of them. Two tone Levi Sta-Prest, fluorescent lime green socks, brogues or DMs, checked button-down Ben Sherman shirts. Two of them had black Harrington jackets with the red tartan lining but I couldn’t afford one on me paper round money. Scarves were out. OK, then, if you had to wear a scarf, it could only be a silk scarf with Trent End or NFFC on it. Round your neck like a cravat. But the real object of desire for everyone was a black Crombie overcoat. The fashion was to wear them with a pocket square in club colours. In fact the square was a piece of cardboard with a couple of pieces of material stapled to it. However, it looked good in your top pocket if held in place with a tie pin. Bizarrely, I bought myself the cardboard pocket square but never owned a Crombie.

Our hero was Ian Moore. We’d get ourselves into the Trent End as soon as it opened at 1:30 and start singing his songs. We’d stand just behind the goal; the older, more vocal Trent Enders had the space right at the back. We’d pretend to be big and swear at the opposition keeper and we’d join in with everything the Trent End sang. Ian Moore, Superstar. Viva Ian Moore. Ian Moore, running down the wing. And maybe also one for six foot two, eyes of blue, Sammy Chapman. That was when Duncan McKenzie was getting a few games and starting to make an impression. We noticed him.

It was only a few bob to get in, yet some of the lads always went in as under 13s cos it was even cheaper, even though they had beer on their breath. I didn’t have the front to try, even though I was the youngest. 71/72 was relegation year, yet my first game was a magnificent 4-1 defeat of West Brom. Martin O’Neill’s debut. Ian Moore scored, of course, but so did Duncan McKenzie. Then McKenzie was dropped again as we went on a run of one win and two draws from the next 14 league games. Relegation form. Robbo was in and out of the side too. Manager Matt Gillies didn’t trust the kids. As Duncan McKenzie told John Brindley: “It wasn’t just me who suffered. We had Alan Buckley, Graham Collier, John Cottam, and, of course both a young Martin O’Neill and John Robertson on the books but Gillies didn’t want to know.”

One of the Villa lads at school wrote all of the results from that run on a desk in our classroom. Not that they could shout – Villa were yo-yoing between the second and third divisions in those days. The last game of that 14 game run was the worst. Worse than losing 4-0 to derby. March 11th 1972. Ipswich at home. McKenzie was in the team, but Ian Moore wasn’t. He was at the baseball ground with a Mr Clough and a Mr Taylor being shown off as derby’s latest signing. He didn’t end up going to derby, but those of us watching the game didn’t know that. Not that there were many of us at the City Ground. The Burton lads were wise and cried off. In the Trent End, there were about 15 of us, huddled together for warmth, singing “Bring back, bring back, oh bring back our Ian to us, to us.” We lost 2-0. We got a bit better after that but still went down. Duncan McKenzie was becoming more important for us – he ended up with 10 league and cup goals that season. Only Ian Moore scored more.

72/3 didn’t start any better and Matt Gillies was soon replaced, with Dave Mackay arriving at the beginning of November. Good managers like Mackay will always give flair a chance. Mediocre managers prefer to play safe. For Gillies and Mackay think Hughton and Cooper. For McKenzie, think Johnson. McKenzie says Mackay arriving was “like being let out of jail.” (For Duncan McKenzie and jail, think Joe Worrall and ‘… like a whipped dog, if you treat any dog with kindness they become a nice dog’.) Mackay sent McKenzie off to Mansfield to get games under his belt. After he’d scored seven goals in six games for the Stags, Forest called him back and he was soon scoring again for Forest … and producing the drag-backs and the nutmegs, the flicks and the tricks, the dribbles and the runs … and the entertainment, the flair, and the spirit. He finished the 72/3 season joint top scorer.

In his time at Forest, McKenzie wore every number from 7 to 11. I guess that showed his versatility. Mackay let him play a free role – effectively outside right, inside right, centre forward, inside left, outside left, anywhere, often all in the same game. Neil Martin up front, George Lyall or Paul Richardson providing the engine in midfield, Robbo and Martin O’Neill out wide and Duncan McKenzie floating wherever he wanted to go.

Rosie was a Villa fan. When she wasn’t wearing her school uniform, she wore pink and light blue. Pink lipstick and sky blue mascara. Tight pink sweaters and a light blue bomber jacket. It was 1973. The church youth club was the only action in our town on a Saturday night. We’d play table tennis and listen to Bowie albums or the Four Tops’ Greatest Hits. We’d have to sit through a sermon at 9:30 so they’d let us in the following week and then we’d leg it home to catch Match of the Day. That youth club is where I met Rosie. She was shy and not sure of herself. Just like me. But I couldn’t take my eyes off her. She was smartly dressed and had a beautiful innocent face. I kept staring at her. She’d sigh like Twig the Wonder Kid and turn her face away. Fortunately, our mates made sure we got together. If they hadn’t I probably would never have spoken to her. There were about six or seven of us in the backroom – lads from the boys’ school, dames from the girls’ school – listening to albums and talking about Bowie. One by one they all got up and walked off, leaving just the two of us: me and Rosie. A boy and girl talking new words that only they can share in.

After that, we saw each other whenever we could. I’d meet her after school, sit in the cafe in town talking and drinking tea and then we’d walk back to the top of her road holding hands. And Saturdays … well she would just have to share me with Forest. Some days I’d go to the game, some days I’d see her. We’d catch the train to Birmingham, go window shopping and hang out at Silver Blades ice rink. Rosie in her long black skirt or black slacks and tight pink sweater. Me in my Levi’s and Ben Sherman. We didn’t do much skating, just a couple of laps round the outside. Mostly we hung out, checking out the clobber everyone was wearing, talking, and listening to the music they played. All the best Trojan ska: Desmond Dekker, Harry J All Stars, Dave & Ansel Collins; and Motown: the Four Tops, Martha Reeves, Junior Walker. And then, the next weekend, I’d be at the City Ground. I split my weekends between Rosie Jones and Duncan McKenzie, but, to be honest, it was Duncan McKenzie’s name not Rosie’s that I wrote all over my school books.

1973. Fashions were changing. Everything was getting bigger. Hair was getting longer. Trousers were getting wider. I got myself a pair of Oxford Bags. Very handy for hiding scarves down inside your trouser legs at derby station. By 73 scarves were in fashion: a scarf round your neck, a scarf tied to each wrist, and a couple of scarves hanging from your belt. Forest still had the red shirts, but now with David Lewis’ tree replacing the stags. The vocal support moved from the Trent End to the East Stand, in front of the seat boys, about two thirds of the way towards the Bridgford. The shops on Arkwright Street were disappearing; in a year or two, they’d just be piles of bricks left here and there so as to be handy for the twats to lob at away fans. Bowie broke up the band just after me and Rosie saw him at Birmingham Town Hall. Meanwhile on the Trent, although we didn’t know it at the time, Forest were starting to get their band together…

The start of the 73/74 season. A lad called V.A Anderson played at left back in a pre-season friendly at Walsall. A lad called A.S Woodcock was substitute in a pre-season friendly at Lincoln. Ian Bowyer played his first game in October after arriving from Man City (Blackpool away, 2-2, scorers: McKenzie & Bowyer). That’s five of the miracle men at the club already. Now get a good manager, tighten up the defence, and let’s see what happens.

1973/74 – a good season. Almost a great season. Everyone will tell you that 1973/74 was Duncan McKenzie’s year. Duncan, Duncan. Duncan, Duncan. Born is the king of City Ground. He was unstoppable. He played pretty much every game. Doing what he did best. Dazzling us in the stands and bamboozling the opposition on the pitch. Finding space where none existed. Beating defences. Performing acrobatics. Mesmerising defenders. Making goals and scoring goals. His mop of hair, his long sideburns, his cheeky grin, and his one, long-sleeved, red arm raised in celebration. 26 league goals that season.

We were a bit unpredictable at times. We had good runs and bad runs. Dave Mackay left to manage a small club near Burton and we lost 2-1 at home to Villa (scorer: McKenzie). We were winning again by November. New manager Allan Brown inherited a good team, with Duncan McKenzie providing the energy, the invention, and the goals. A run of 8 wins and 7 draws in 18 games took us to two points behind the promotion places with a game in hand. Middlesbrough were runaway winners of Division 2 that year, yet we beat them 5-1 at our place. Graeme Souness in the Boro midfield didn’t get a kick. We couldn’t believe how good we were, me, Les, and his mates. And I can still remember the look of surprise on Bernie Winfield’s face when he scored, right in front of us in the East Stand, just like Jack Colback’s against West Brom.

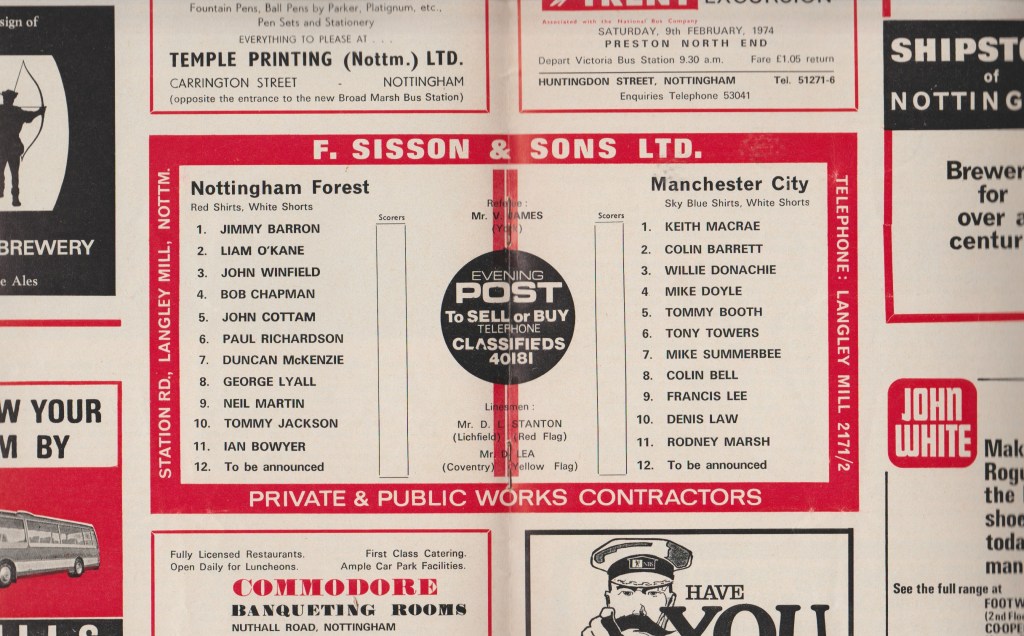

The highlight of the year was McKenzie’s Game. Say “McKenzie’s Game” to anyone my age and they know what you are talking about. Sunday January 27th 1974. The day Duncan McKenzie beat Man City. A City team with Colin Bell, Francis Lee, Rodney Marsh, & Mike Summerbee (& Colin Barrett) beaten by Duncan McKenzie.

Even the City players applauded him. Even Man City fans appreciate what he did:

“The first was scored from close range after some McKenzie wizardry on the flank had made space for him to ping in an accurate cross. McKenzie himself got the second, then laid on the other two to seal Forest’s humiliation of the Blues.” (Man City blog)

“Forest’s third showed all of McKenzie’s latent talent, as he dribbled past the bemused Donachie, doubled back to beat the same man again, then rounded Mike Doyle and Tommy Booth before clipping the ball back to give Bowyer his second of the afternoon. ” (Man City blog)

“[I] remember the pitch being very muddy & Mckenzie floating across it, he really took the piss that day.” (comment on Man City fans web page)

That year could have been so much better. We should have got to Wembley and we should have won promotion, but we got robbed in the Cup, royally robbed by Ted Croker’s FA and Newcastle United, and we finished 4 points short of promotion after fading away at the end of the season.

The last time I saw Duncan McKenzie play for us was at Villa Park. I wasn’t seeing Rosie any more – we’d drifted apart as we got older. As you do – you change a lot at the age of sixteen. This was April 1974. There was still a slim chance of promotion if we won our remaining games and other results went our way. Tony Woodcock made his debut. Duncan McKenzie scored, of course, but we lost 3-1. Yeah, I know. If we’d have won our league games against Villa that season, we’d have been promoted. Rather than build on the team that nearly made it, Forest decided to cash in on McKenzie’s talent and he went to join Clough at Leeds.

Everyone appreciated Duncan McKenzie. (Well, everyone apart from a certain Forest manager.) Leeds fans will tell you that signing Duncan McKenzie was the only good thing Clough did for them. Everton fans will tell you how good he was when they bought him. Blackburn Rovers fans will tell you the same. But Duncan will always be a Red.

Staying back in your memory are the movies in the past. Rosie Jones is always waiting for me outside the caff next to the bakers. David Bowie is always on the turntable singing about Ziggy and Star men. And Duncan McKenzie is always in red; strutting his stuff at the City Ground. Dribbling past defenders, making goals, scoring goals. Having fun, doing his tricks, making fools of the opposition. Playing for the hell of it, playing for one simple reason: because he could.

And boy he could play. Like no-one else.

(Match stats from Ken Smales. Song lyrics from David Bowie.)