An Eclectic Circus

Chapter 23

Take a chance with a couple of kooks

Fi and Cat got a flat over in Bruntsfield. Bruntsfield Terrace, right on the corner. Second or third floor. Great position. It would be the ideal place to sit in the front room and watch the folk down on Bruntsfield Links. Look out at the bat church just visible down Bruntsfield Place and see if that angel was looking out from up the spire. I did see her once, one evening as I was passing. The sky was getting dark, so the church was mostly a silhouette, but you could see her angelic outline next to one of those wee turrets that look like a bat’s ears on each corner of the spire. Problem was, we never sat in the front room at the Bruntsfield flat, hardly ever, always in the kitchen. That’s where Fi and Cat had the TV. We’d go round there to watch Top of the Pops because no-one else had a TV. We didn’t get one at the Palace until May. Just in time for the European Cup Final. We got the washing machine first and then debated whether we could afford a TV for ages. In the end we rented one at about £9 or £10 a month mainly so I could watch the football. We didn’t watch TV much. Just Top of the Pops. We did, one evening, go back to the Doric and sneak in to watch James Dean on their TV. That one with the oil wells. Giant. That would have been November, after we got the Palace of Marchmont but before Fi and Cat got Bruntsfield. The Cat and Fiddle we called it, their place. They served great tea.

Fi and Cat are a right pair of imps. They’re younger than the rest of the Dorics. Ages younger than me of course, but younger than Pete and Gav and Nessie on account of kids in Scotland do their Highers one year earlier than kids in England do their A levels so they end up going to University one year earlier. Apart from Gav, who stayed an extra year at school for some reason that never became clear to me. They’re from somewhere over the Forth Bridge in Perth, Fi and Cat. They’ve known each other all their lives and are kind of like a double act, plotting stuff together in secret whispers and asides and then laughing out loud at jokes only the two of them can see. Kind of like twins with a secret language.

Gav calls them the Wee Fis. That’s “Fis” as in “Fees” not “Fis” as in “Fizz”. It’s a Scottish joke. Apparently. Or is it spelt “Fies”? Dunno. Gav never wrote it down. I called them the Banshee Twins. They were both into the Banshees, so not very imaginative. Fi was tall and thin with short black moppy top hair and kohl black eyes, but more Pauline Murray than Siouxsie Sioux. Cat was not so tall but just as thin with short blond moppy-top hair and kohl black eyes: more Steve Severin than Siouxsie Sioux. Fi wore a leather jacket for the Gaye Advert image or an old men’s jacket – that’s where Pauline Murray came in. And they both wore narrow drainpipes, though I did see Cat with bondage pants once. At a party. And Cat had those fuzzy mohair sweaters that were popular back then.

For me and Alex, people our age, punk was an event. A single act that blew the doors off. A moment in time. Like the iridium layer that marks the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary when folk stopped listening to the dinosaurs and started grooving to the mammals and the rest of the new life. Punk didn’t so much twist the kaleidoscope as smash it into pieces and throw all those coloured bits of glass all over the house, so you got bits in your carpets and bits in your hair; flashes of yellow, red, blue, green, & violet on your shelves; fragments of purple, orange, & turquoise in your hair; grains of ochre, topaz, ruby, & emerald under your fingernails; slivers of indigo, sienna, amber, amethyst, azure, crimson, fawn, vermillion, garnet, magenta, jasmine, lavender, lemon, lime, apricot, jasmine, pink, sapphire, tangerine, mustard, and loads more stuck behind the sofa. Pieces of colour everywhere that you’d still be finding ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years later.

We’d embraced punk after it started, sometime at the end of 76. We’d changed our clothes, our music, and our outlook. But when punk died, sometime before the Pistols managed to release their album, we’d moved on to all the new stuff.

I look back at punk and think: well done, now let’s move on. Some moved on: the Clash got better and better. Buzzcocks got better and produced some first class pop. The Jam got better. Other folk stayed where they were. Or never really were there in the first place. Or were somewhere else better in the first place like all the American bands: Television, Blondie, Talking Heads. By 1979, you had to be a Magazine or a Banshees or an Only Ones to make an impression.

We kept the narrow trousers and the thin ties. We kept our hair shorter. We pushed the old dinosaur albums to the back of the LP shelf. And we embraced the next big thing. Imaginatively called it post punk and thought it was avant garde.

For Fi and Cat, punk was more important. They were 14, 15 when it took off. It became embedded in their souls. Like the music I listened to when I was that age is embedded in my soul, even now. Bowie & Roxy. The Four Tops and the Temptations. Rod Stewart’s early albums. So it is with Fi and Cat and punk. It defines them. For them it was something much more important than it was for me. A way of life. A confirmation of self. Something that will live with them forever. That’s why they treat it as so much more important than me and Alex and Pall and other folk my age do.

Cat says: “For our generation, everything flowed from punk rock. Punk was way more important than situationism, post modernism, or any of your bagism dragisms. Who remembers Debord or Marcuse? Everyone knows Rotten & Strummer.”

So, they’ll always be punks at heart, Fi & Cat. They were both into the Banshees and Buzzcocks, although if you tried to talk music with them, they’d just go on about the Skids, and the late great Rezillos. What I jokingly started referring to as junk jock punk rock. Twenty million miles of bleakness; human weakness. It took me a while to see that their camping up of the “only Scottish stuff matters” vibe was all a bit of a windup. But I love it. Destination Venus is an absolute classic. And they did introduce me to some great Scottish music.

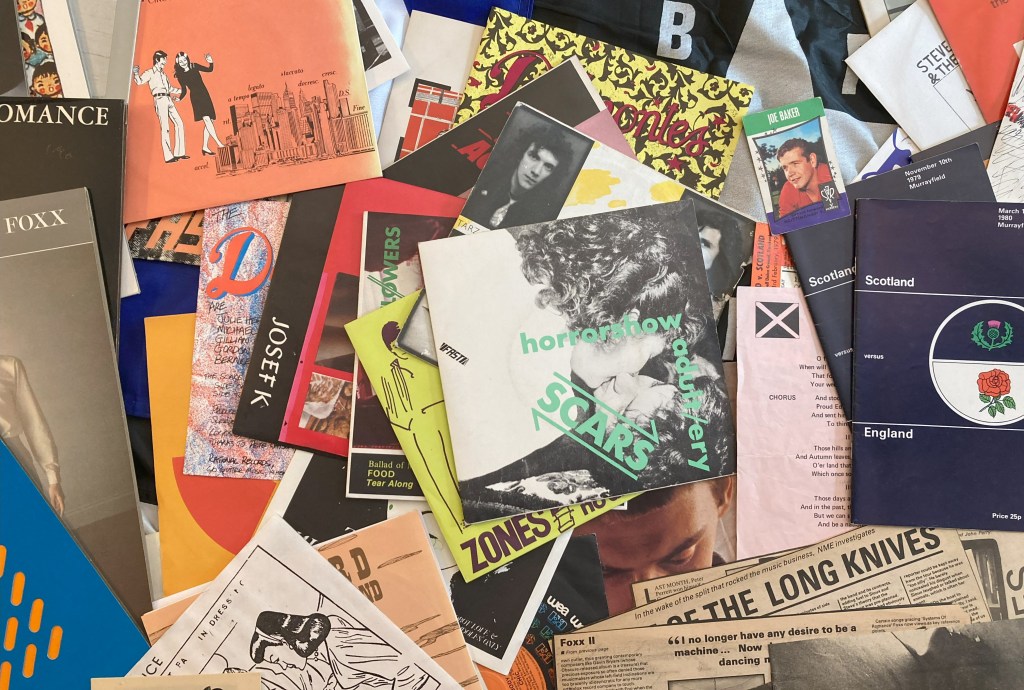

- The Jolt. More of an R&B band to begin with – feeding off the Hot Rods and the Feelgoods. Then picking up on the 60s sound and look in the same way that the Jam did. The Jam had the classics from the start (In the City, Away from the Numbers) and had the better suits so the Jolt suffered by comparison. They moved down to London which didn’t do them any favours, either in Scotland or down south. The singles were rough and punky: much better than most of the lame mod revival tosh that surfaced two years later after the Jolt had split. Their album wasn’t bad – better than the Jam’s second album, although that isn’t hard. “I Can’t Wait” wouldn’t have been out of place on the first Jam album. In fact, any track on the Jolt album would’ve been better on the Jam’s first album than the Batman theme.

- The Valves. Another early Scottish “punk” rock band, the Valves unsurprisingly started life in the early 70s as an early 70s proggy long haired early 70s pub rock band. Spotting the band wagon leaving in mid 77, they jumped on board, changed their name and their style (but not their haircuts) and produced six sides of above average punkish R&B and R&Bish punk rock, including the wonderful Ramones classic Ain’t no Surf in Portobello. (Although, as far as I know, the Ramones are yet to record it.) You could make a pretty good case for all of the Valves B sides being better than their A sides. But, to be honest, those six sides are fun. You can pogo to them. I can see why Fi and Cat liked them.

- The Scars. One of the few, if not the only, Scottish band on Fast Product. Their single had two great sides: Horrowshow with its violent scary guitars and repetitive and mesmerising Mark E Smith vocals. And Adultery: bass driven and skittery Gang of Four guitar. Excellent.

- The Zones. Formed 1977 out of the dregs of punk one miss wonders PVC2 who were themselves formed out of the dregs of bay city rollers tribute act Slik who used to bother TotP with their baseball uniform wearing antics. Released one fairly decent punk single on Bruce’s very own Zoom records (Stuck with You) and one lively power pop/Roxy Music style single (Sign of the Times) after signing with Arista in mid 1978. After that, they reverted to bland plodding pop radio fare and dissolved sometime in the winter of 79/80.

- The Cheetahs. Another one of Bruce’s Zoom Records bands and a personal favourite of both Fi and Cat. Released a decent punky single (Radioactive) then disappeared, taking Zoom Records with them. The single was recorded in a Bruntsfield flat. The same one that the Rezillos used. Fi claimed it was their Bruntsfield flat. (In fact, we think it was across the links in Barclay Terrace, but does anyone really know for sure?)

- The Zips. A Glasgow band that made a great EP: two tracks of punky pop, much stronger than any of that power pop guff that came out of the south (like the Pleasers) or the west (like the Knack) and two R&B tracks: 101ers meets early Hot Rods. Unfortunately no-one ever had it cos they released it themselves and only made a couple of copies so all Fi had was a tape from a Peel show. If they’d had been on Zoom or Fast they would have been so much bigger.

They had me go up and see them for New Year’s. Just before I went swanning off round the South Atlantic. Fi and Cat that is, not the Zips. I stayed with Fi’s folks in an old school house in this small town up near Perth. New Year’s Eve we all went out late and watched the town folk run around the place with massive great torches. Then after about 12:30 or so, we just wandered around going into all these houses. The doors were left open and the folk in the town split into small groups of about four or five and went from place to place, sometimes bumping into other groups, comparing notes, sometimes sitting in someone else’s front room chatting, helping themselves to a wee drink from the drink’s cabinet or kitchen table. It seemed to me that sometimes the owners were in and sometimes they weren’t. Fi and Cat seemed to know everyone though. Not just the kids their age that they must have been at school with, but also the older siblings, the parents, and even the grandparents. I got fussed over – being English, everyone wanting to make me feel welcome and included. Pity I couldn’t hold as much drink as they all could, though. And I suffered the next day when they took me up some local hill to pay respects to some old boy from the university. Apparently he’d been a big noise under William Pitt.

When I left, Fi’s Dad took me to one side and pressed my hand. He told me that the noble tradition of hospitality was deeply rooted in each Scottish breast and that I’d always be welcome. I wanted to let him know I was grateful, but not having the words or the quotes to do justice to his comments, all I could do was mumble “Thanks.” I told Fi how much it meant next time I saw her. I told Cat about it later, too. She said:

“The auld folks all say that back home. D’ye know why?”

I said: “I guess it’s because they’re proud of being welcoming.”

She said: “It’s also because they’re proud of being Scottish. The habits and principles of the nation are a sort of guarantee for the character of the individual.1“

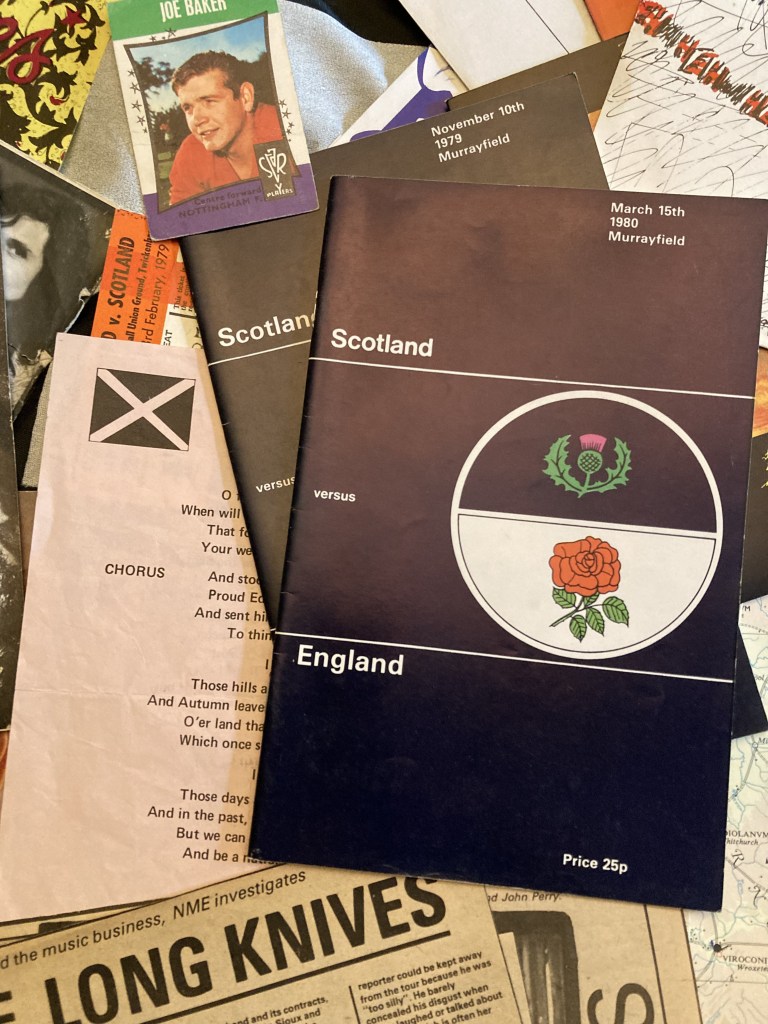

Not content with introducing me to a great many wonderfully welcoming Scots back in Perthshire, Fi introduced me to the other side of her fellow countrymen and women. This was later – March 1980 soon after I’d got back. She had me meet up on the Mile one Saturday, near St Giles, then suggested we have a drink at Deacon Brodie’s. I’d not been in there before. It was full of kids – kids she knew from school and kids they knew. They were down for the game. Scotland England at Murrayfield and she’d got me a ticket. Someone she knew couldn’t go. And she suggested out loud that I go with her mates.

“This is the Ned from the hotel. He’s my good mate from England. Will you take him to the game and look after him, please.”

The initial reaction was one of laughter and insult. I got called a few names, the politest and most common of which was the Scottish word for a Saxon which would be fair as I almost certainly have Saxon blood. Then the atmosphere became strangely subdued. Some of the lads started staring into their beers and began whimpering about how much they could have achieved if it weren’t for us Sassenachs. How I’d stolen their oil. Me personally. Like that scene in Trainspotting where Renton summarises his feelings of love for both the Scottish and the English. Then the lads from the East Terrace at Hibs turned up and took up their standard refrain to prove that they were in good voice for the match. Away back home, you Sassenach bastards and so on and so forth.

Later that year – in June of that summer – it’d been the European Championship. I’d made the mistake of watching the England Belgium game up at Kings Buildings in the Student’s Union. I got so much grief. Compare that with two years before when Scotland played Holland in the 78 World Cup. I’d watched that game at the Union in Southampton. The cheer that went up when Archie Gemmill scored was deafening. And the reaction in Scotland to Wilkins’ goal against Belgium was the complete opposite. It was a lovely goal, too. We should have won that game against Belgium. Tony Woodcock scored a winner right at the end but some fool lino invented an offside from somewhere. Not that the rest of the TV room agreed with me.

So I left the folk at Deacon Brodie’s and walked down the Mound on my own, over to Haymarket, past Donaldson’s to the ground where I was met by some folk helpfully handing out songsheets covering both Flower of Scotland and God Save the Queen. The 1745 version of God Save the Queen with the verse about crushing rebellious Scots.

Strange thing is, I was making a habit of stumbling over tickets for the Calcutta Cup. The year I was in London, the year before starting at Edinburgh, I stumbled across a ticket for the game at Twickenham. And a few years later, we got a couple for the 33-6 annihilation at Murrayfield. That was painful. Why on earth do I get so emotionally involved in these games? Why do I care so much whether England win or lose? We were in the South Stand in front of the clock tower and I swear all those folk from Deacon Brodie’s were there laughing at us. Away back home, you Sassenach bastards and while you’re there you may want to reconsider what you were thinking about when you came here in the first place and so on and so forth. Taffy Smith from school was on the pitch and I don’t think he enjoyed the game any more than we did.

The Twickenham game in 79 and the Murrayfield game in 1986 are best forgotten. However, that afternoon, March 1980, the Calcutta Cup game was wonderful. There were some great names on the pitch… Roy Laidlaw, Jim Renwick, Andy Irvine, Bill Beaumont, Clive Woodward, Dusty Hare, and many more … there was some great rugby played by both sides, plenty of exciting running from both sets of backs … and England dominated. 19-3 up at half time, 30-18 at full time. Grand slam won. We could go home happy.

What I did, though, was to call in on Sarah and Maggie who had managed to get a room each in this massive house somewhere between the ground and the West End. The thing I remember most about the place was the enormous kitchen with a dirty great big Aga on one side, a gigantic oak table in the middle, and pots and pans hanging from the ceiling. They were sat there drinking tea with their landlady, listening to some of Sarah’s folk stuff. I’d wanted to catch the football results, but I bit my tongue rather than ask for them to switch the radio. So my euphoria after the England game lasted another hour or two before I got back home and had my mood severely dampened by hearing about Peter Shilton and David Needham’s exotic ballet on the pitch at Wembley during the League Cup final. Why on earth do I get so emotionally involved in these games? Why do I care so much whether Forest win or lose?